Researching the women of early medieval England on the web

I often get emails from subscribers who are doing their own wonderful research into early medieval women, or are asking for advice about how to do so. While sadly a lot of historical information is more accessible if you have academic training, a lot of money or a university library membership, the whole point of Ælfgif-who? is to bring what we know about women in early medieval England to a wider audience.

This post will reveal a number of ways you can conduct your own research, on the web, for free, by accessing primary source material (sources from the early middle ages) that has been entered into searchable databases online. I use these free resources constantly in my academic research, but they’re also just very fun to play with, especially if you have a family or local connection and want to find out more about a specific person or place.

PASE (Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England)

PASE is an online database that records all known inhabitants living in England from 597 until 1066 and beyond, and the sources where they're mentioned. It is run by scholars from King’s College London and the University of Cambridge. You can use PASE to search by name, date or location, or even people involved in a specific event. ‘Prosopography’ is the study of groups of people, in other words collective biography - but this database is great for researching individuals too.

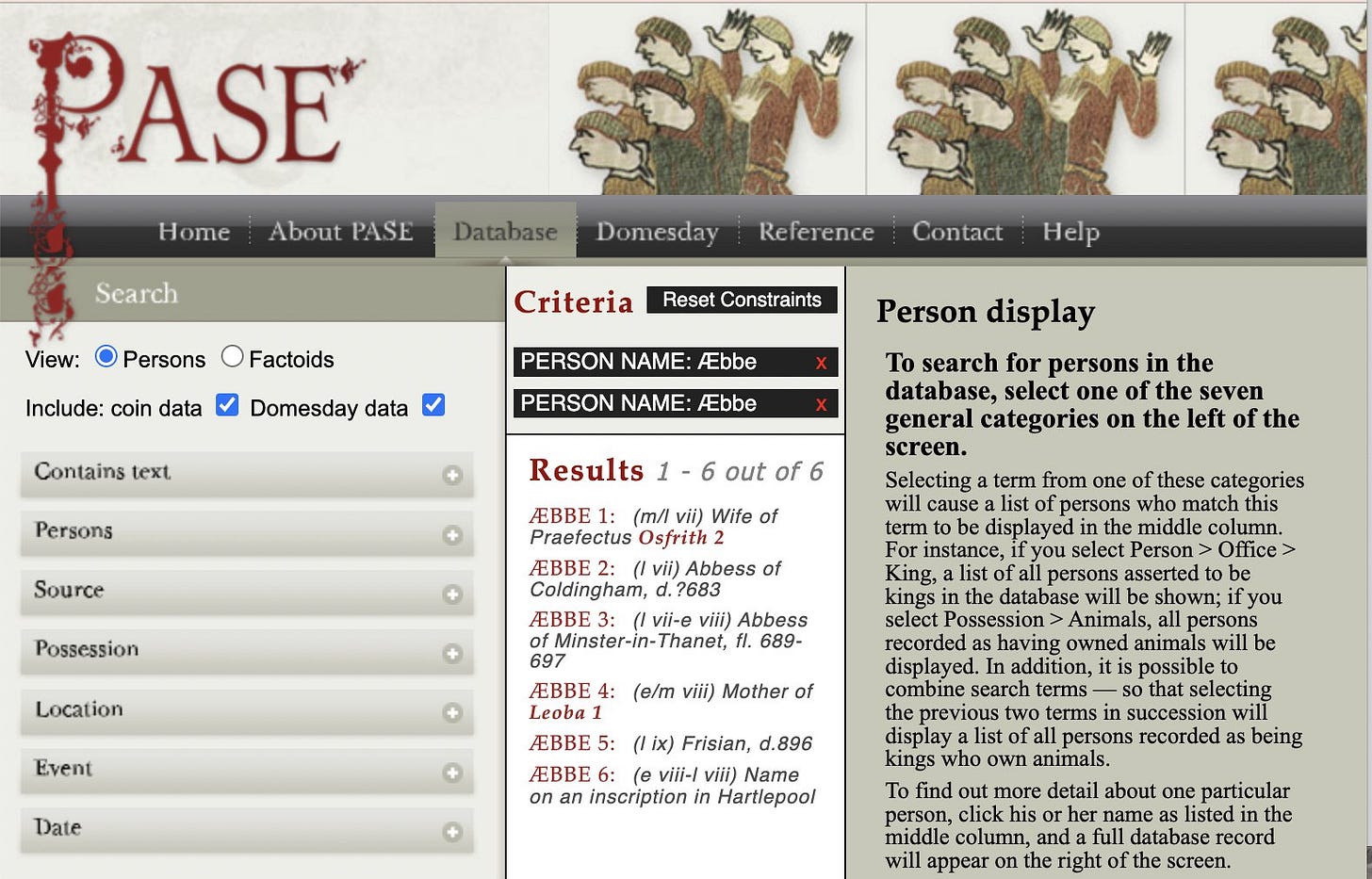

For example, here's a screenshot of my search for a woman called Æbbe:

There are 6 results, which may refer to different women or the same woman. Clicking on any of these records for women named Æbbe will expand further details, for example occupations, people she is related to, events she is linked with, and any information known about her.

There are 1460 women in the PASE database, which is the upper estimate of how many women we have some data about from this period, though many of these records will inevitably overlap. Another fun thing to do is to pick a meaningful location, for example for me this would be York, and look up all the women linked with that location. There are 317 results to browse for York.

Open Domesday

The Open Domesday is a website that allows you to search for either names or places recorded in the Domesday Book - a record of all land ownership in England before and after the Norman Conquest, compiled under William the Conqueror. You can also search on an interactive map. The site was built by Anna Powell-Smith using data assembled by a team of researchers from the University of Hull.

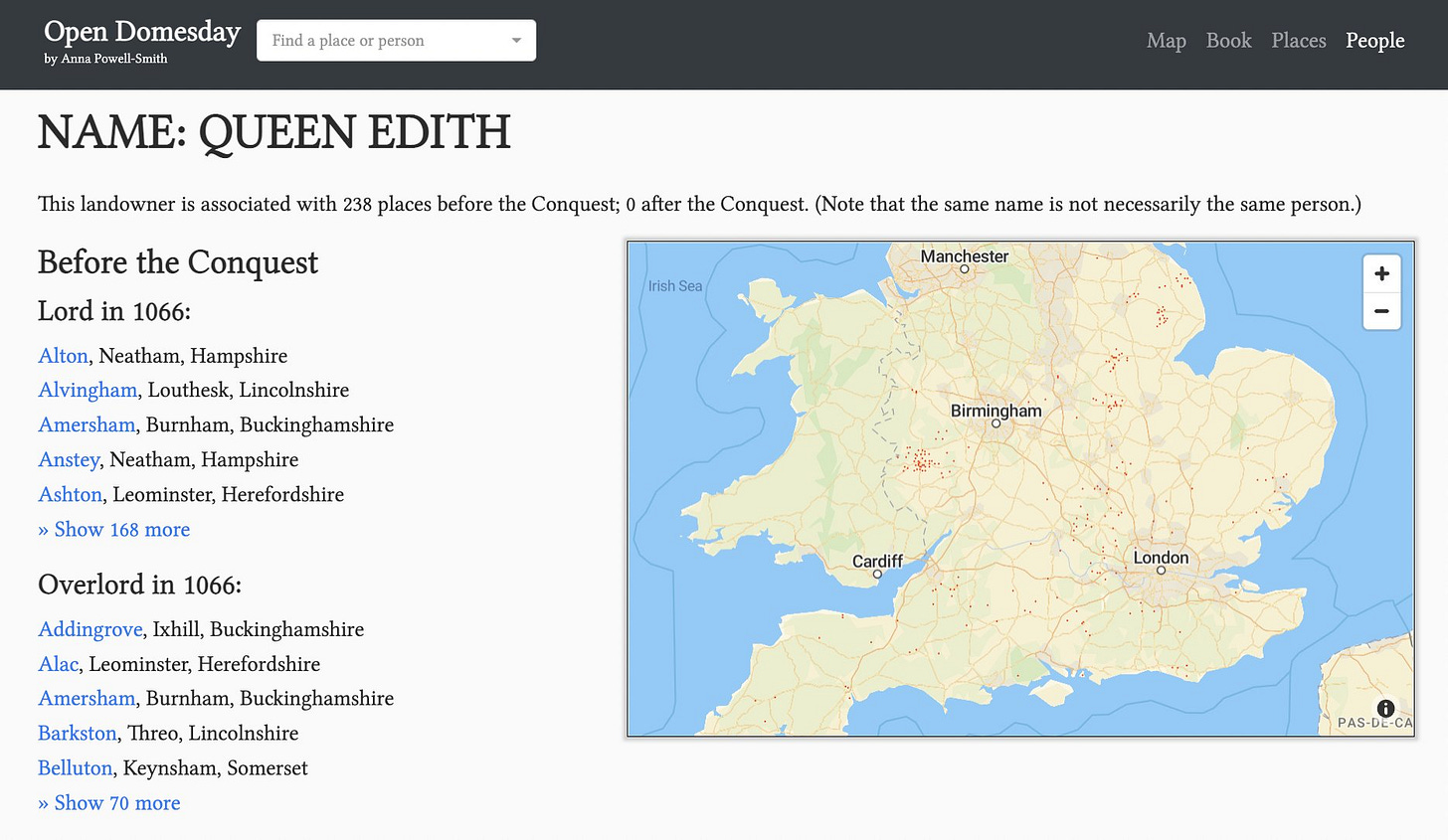

For example, here is a screenshot of my search for land owned by Queen Edith:

As you can see, Edith owned a lot of land all over England, and there are hundreds of results to browse through. Instead, you could search for a specific area and find out who owned it before and after 1066.

Epistolae

Epistolae is an online collection of translations of Latin letters to and from women in the Middle Ages, from the 4th to the 13th centuries. It is searchable by sender or receiver. The database is a collaboration between Professor Joan Ferrante of Columbia University and the Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning.

This resource has been invaluable for researching women who are only known by letters they sent or received, like Leoba.

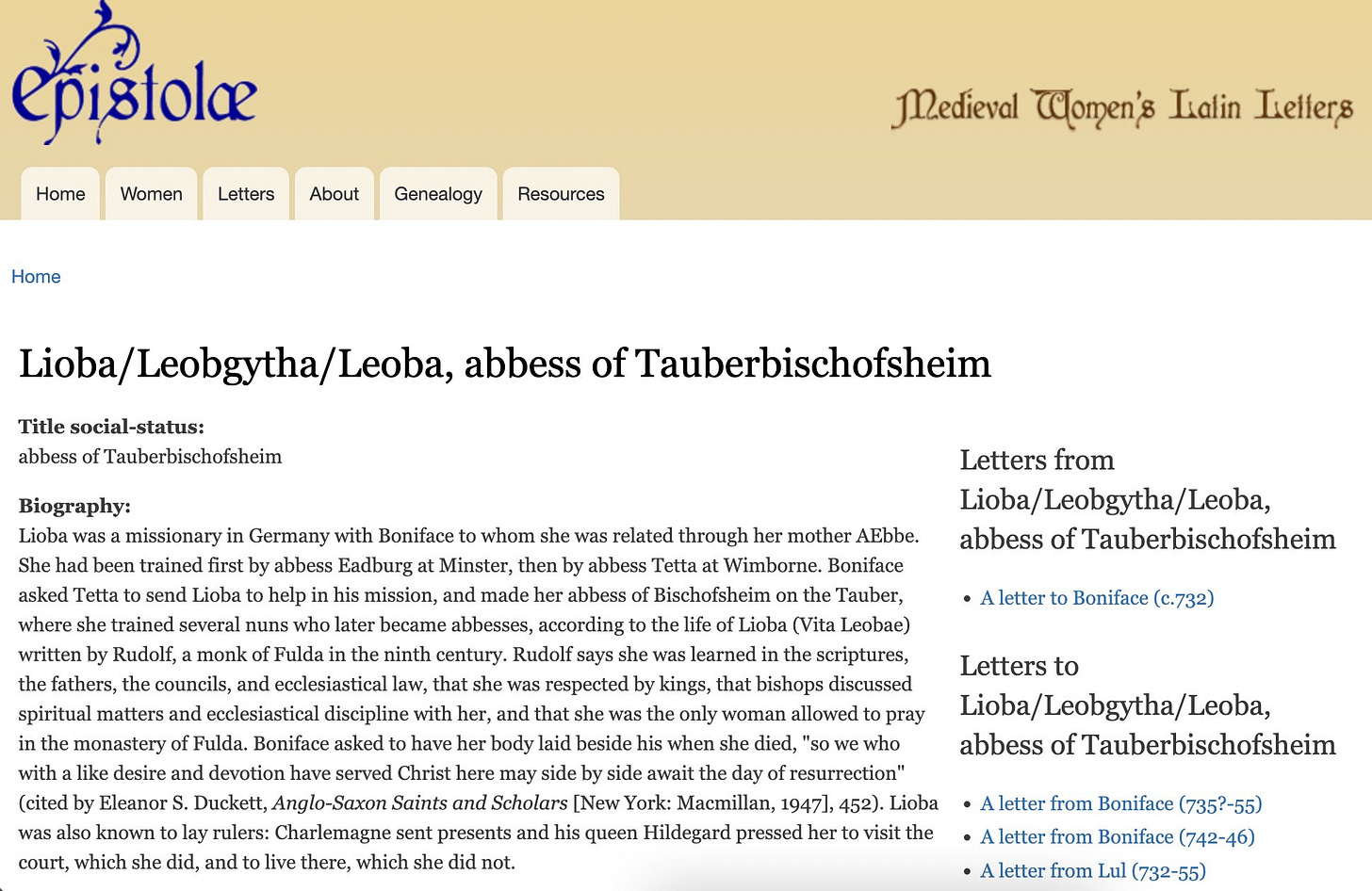

For example, here is the result for a search for letters to/from Abbess Leoba:

The database not only provides a short biography of Leoba, but on the right hand side of the screen you can see links to translations of letters sent between her and others.

The Electronic Sawyer

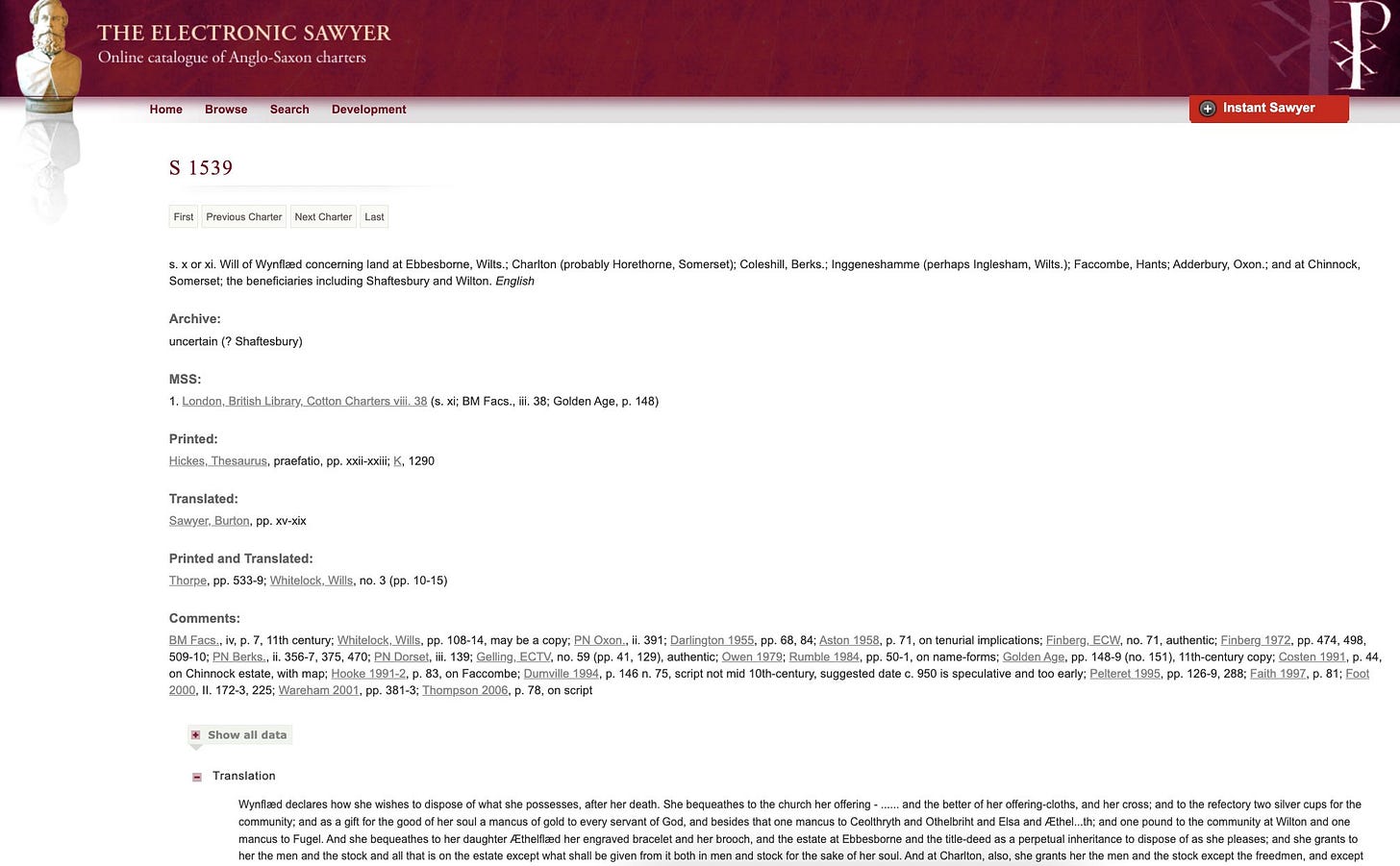

The Electronic Sawyer is an online catalogue of charters produced before 1066. It’s a searchable and browsable form of a revised, updated, and expanded version of Peter Sawyer's Anglo-Saxon Charters: an Annotated List and Bibliography, published by the Royal Historical Society in 1968. I have found I sometimes encounter tech issues while using this site, but if you can figure out how to use it you can search through documents by date/king's reign/keyword. Each charter or document is listed with an identifying ‘Sawyer number’.

The Sawyer database is very handy as it provides indications of whether or not a source is trustworthy - for example, it will alert you if a charter is considered by scholars to be a later forgery or if a source has seemingly been tampered with.

The Key to English Place Names

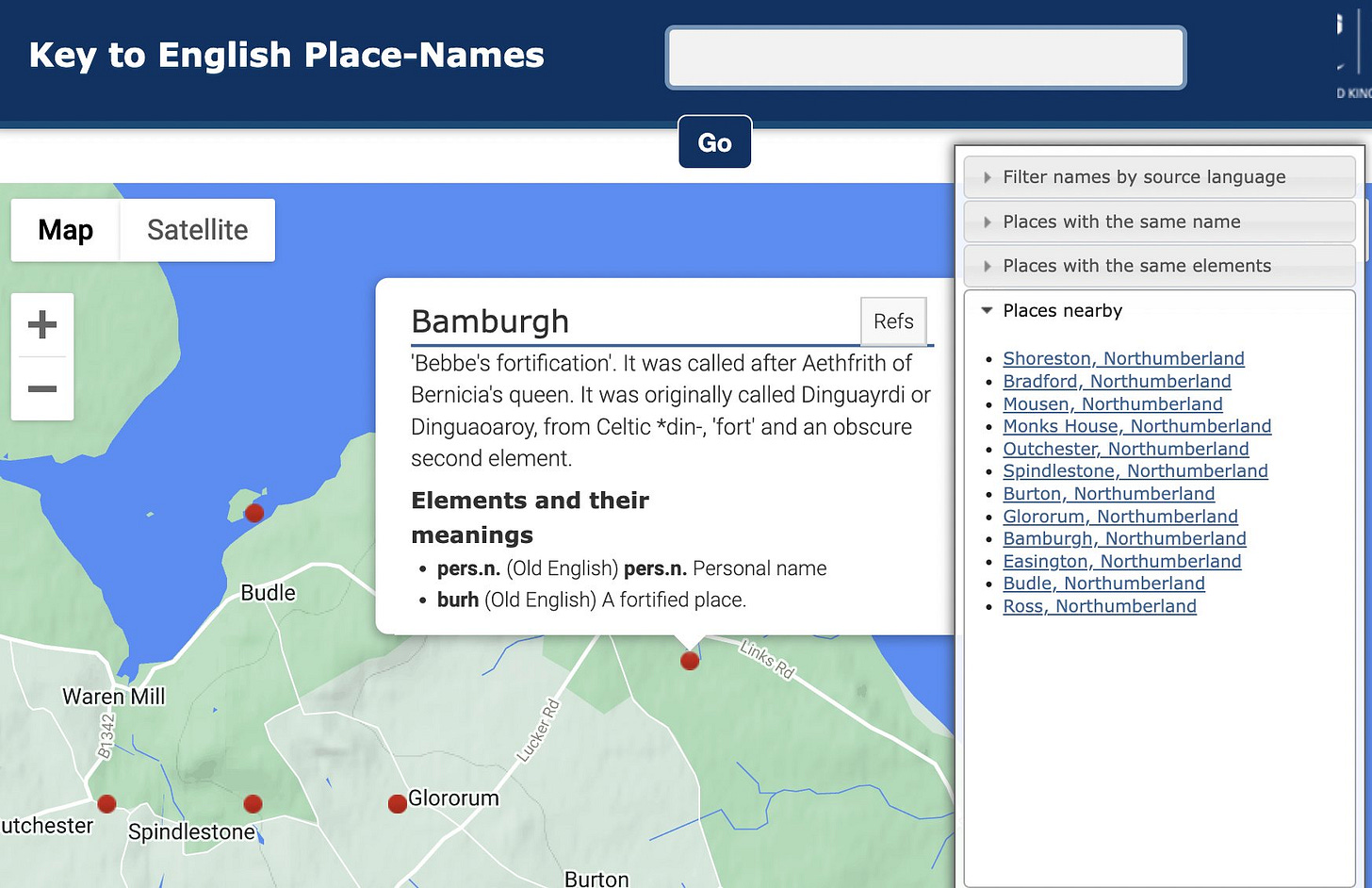

The Key to English Place Names is an interactive searchable map and database providing origins and meanings for hundreds of English place names developed by the University of Nottingham. You can search for a particular place using either a text bar or an interactive map and what is known about the meaning of the name will be revealed. This is particularly good for researching women who are known to us because of their connection to a place, like Queen Bebba.

For example, here's a screenshot of the search result for Bamburgh:

Place names can often tell us something important about the history of a place, and they’re also just fun to learn about.

In my ideal world all historical knowledge, information and research would be digitised and freely available to everyone, with the researchers themselves being well recompensed for their work. Until then, I will work to highlight the projects that are making history accessible. If you use any of these resources to find out something interesting about a medieval woman, a local place or an interesting historical event, please do let me know in the comments! I would also love to know if there are any useful historical tools you use to do historical research.

Hi Florence - fantastic resource, thank you. Another way you can contribute to history becoming more accessible is by volunteering as a transcriber which is what I have been doing here in Australia through various libraries and museums. It is hugely rewarding in the giving and receiving of historical information. I am sure there must be similar things in the UK??

Thank you so much for sharing these! I love studying medieval history, but I only use secondary sources. I’m unfamiliar with how to find and use primary sources. So this was eye opening and very exciting. I start grad school this fall and look forward to learning more about diving deep into medieval texts and how to learn from them.