Ælfgif-who? provides short biographies of early medieval English women every two weeks. Click on the podcast player if you’d like to hear this newsletter read aloud in my appealing Yorkshire accent.

Emma, Part 1: A Queen of England Twice Over (c.980-1035)

Queen Emma cuts such an important figure in eleventh-century politics that I took the decision to publish her biography in two parts. This first part looks at Emma’s early life and her two marriages: to King Æthelred II (1002-1016) and King Cnut (1017-1035). Part 2 (the next edition of Ælfgif-who?) will cover her widowhood in 1035 until her death in 1052, including her involvement in the succession crisis following Cnut’s death, her role as the mother of two kings of England, and her commissioning in 1041 of a literary work written in her political defence: the Encomium Emmae Reginae.

Background

Emma was born in Normandy some time in the 980s to Count Richard of Normandy and his wife Gunnor. Her birth date can be calculated backwards from the assumption that she was probably no younger than 12 at the time of her first marriage in 1002, and no older than 40 when she had her youngest child in 1020. Emma was born at a time when the ‘North Men’ that Normandy was named after were still a very recent memory: the legendary Rollo, the first Scandinavian ruler of Normandy, was her paternal great grandfather. Count Richard had allowed Vikings to use Normandy as a base in order to raid Britain and northern France, and British and Irish enslaved people captured by the Vikings were being sold through the market in Rouen. Emma’s mother, Gunnor, was also Scandinavian: Danish by birth, she was Richard’s concubine after the death of his first wife, and their union was legitimised sometime in the 980s to secure Emma’s brother Richard’s position as his father’s heir. Richard II succeeded in 996, when Emma was certainly still a child, and their mother Gunnor continued to exert considerable influence in the Norman court ruled by her young son. It was at this time that Gunnor and Richard II commissioned Dudo of St-Quentin to write a history of the Norman counts that took pride particularly in Richard II’s Scandinavian ancestry. It is unknown if Emma grew up within this court context, but if she did it is likely that she was imbued at a young age with examples that, as we will see, would benefit her in later life: she would have been witness to her mother’s matriarchal power at court, her family’s assertion of political power through the written word - and crucially, she would have learned to speak Danish.

Marriage to Æthelred II (1002-1016)

It is the context of Viking raids which brings Emma into the historical record, as the young bride of King Æthelred II of England in 1002. Around the first millennium, Vikings who raided southern England were spending the winter in Normandy with Richard’s permission. This did not endear Æthelred to Richard, and in 1001 he sent a fleet to Normandy, probably in the hope of overthrowing the Duke. This attempt apparently failed, and England and Normandy seem to have come to a cooperative agreement in the marriage of Richard’s sister Emma to Æthelred.

Circumstances had conspired to make this union possible: Æthelred’s wife Ælfgifu had either died or been repudiated by 1001, and perhaps more importantly, his mother, the powerful dowager queen Ælfthryth also died around this time. This left a vacuum of female power and room for a new queen. Æthelred used this opportunity to broker the first marriage of an English king to a foreign bride since his great-great-great grandfather Æthelwulf married the Frankish princess Judith in 856. And there are parallels. Emma may have been, like Judith, a child bride, though she could have been as old as 22 when she married Æthelred. Like Judith, her new husband already had a clutch of sons from a previous marriage, to whom her presence was a threat. It is difficult to imagine how it must have felt for Emma when, upon arriving in a new country, her name was changed from the Norman ‘Emma’ to the English name ‘Ælfgifu’, the name of her new husband’s grandmother and his previous wife. While her usefulness to Æthelred was rooted in her own family background (an annalist at the time remarks that ‘in the spring the Lady, Richard’s daughter, came to this land’), this was an identity she had to shed upon arrival.

The marriage did not put an end to the violence between the English and the Vikings. In November of that same year, on St Brice’s Day, Æthelred ordered the massacre of all Danes living in England. A royal charter by Æthelred for the rebuilding of an Oxford church mentions without remorse that it was burned down during the massacre, after the Danes of the town fled inside for safety. The same charter says that the Danes had ‘sprouted like cockle [a weed] among the wheat’ and that their extermination was just. One of those said to have been killed in the St Brice’s Day massacre was Gunhilde, sister of Swein Forkbeard, king of Denmark. In the following year in retaliation for this massacre, and likely also for the marriage designed to put an end to Viking overwintering in Normandy, Swein attacked Exeter, part of the new queen’s dower lands. Though Emma’s lands were the target of this attack, she also received some of the blame: the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle’s annalist for 1003 holds Emma’s French reeve Hugh responsible for the massacre, whom she herself appointed. The assimilation of Emma into Englishness signalled by her name change did not absolve her from blame placed on foreign scapegoats.

In c. 1005, Emma had her first child, who would later be known as Edward the Confessor. By 1013 she had another son, Alfred, and a daughter, Godgifu. Though throughout her marriage to Æthelred she was prominent in the signatory lists of charters, this was no guarantee that Emma’s young sons were destined for the throne. Æthelred’s sons from his previous marriage were adult men, who were increasingly involved in military planning as the Viking threat loomed larger throughout the 1010s. In 1013, Swein Forkbeard conquered England, and Emma and her sons were sent to Normandy. Æthelred followed while his adult sons remained in England. After Swein died in 1014 they were able to return, though with Æthelred’s position weakened it was Swein’s son, Cnut, who now claimed the throne. By June 1015 Æthelred’s eldest son Æthelstan was dead, and his other son Edmund Ironside was rebelling against him. While Cnut continued his military campaign for the English throne, Æthelred died suddenly in April 1016. Though Edmund attempted to fight Cnut he was ultimately defeated in 1016, and died in November of that year. By Christmas 1016 Edward and Alfred were safe back in Normandy, but Emma remained in England. It is likely that she was prevented from fleeing to safety by Cnut.

Marriage to Cnut 1017-1035

Though Emma would later present this union as a consensual one, in which she had bargaining power, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle tells us that in 1017 Cnut ordered her to be ‘fetched’, and they were married. Whether forced or consensual, this marriage presented certain advantages to both parties. For Cnut, he could benefit from the continuity that Emma could provide as the ‘English’ queen Ælfgifu, while somewhat neutralising the threat of her sons by Æthelred. It may also have been something of a personal advantage to Cnut that Emma was herself of Scandinavian ancestry, and likely spoke Danish. For Emma, marrying Cnut allowed her to continue in her position of queen, while keeping her lands in England, and she probably hoped that neutralising her sons would help to protect them. There were complicating factors, though, not least that Cnut had already married an English woman, Ælfgifu of Northampton, in 1014, and she had two sons by him, Harald and Swein. There is no evidence that Cnut had repudiated his first wife, and it is likely that he remained married to both women - though Emma would later claim that her rival was merely a concubine. Once again Emma had found herself in a situation where she was the second wife of a king, vying for the favour of herself and her progeny: by 1018 they’d had a son, Harthacnut, and by 1020 a daughter, Gunnhild.

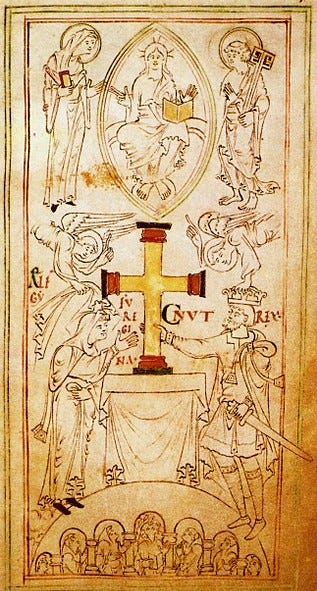

But Emma was not in a position of total weakness. She had now been in England for 15 years. By the time of her wedding to Cnut she would have been intimately acquainted with court politics and the nobility. If Cnut hoped to push for legitimacy through continuity, he was to rely on her. While Emma was a political tool in both of her marriages, her role had been transformed from the symbol of an agreement between two rulers, to an active participant in a political regime. This new role afforded her more importance. She was crowned as Cnut’s queen as a symbol of their partnership. She ranked high on the witness lists of his charters, often jointly alongside Cnut, and as ‘regina’, queen, not as Emma but as Ælfgifu. The clearest symbol of the ‘joint rule’ of Cnut and Emma is their 1031 portrait on the frontispiece of the New Minster Liber Vitae, showing them donating a cross to the Minster - of course she is labelled Ælfgifu. This is the earliest surviving contemporary portrait of a queen apart from Cynethryth’s coin. By the time of her death, Emma would have a second portrait, which will feature in part 2.

Despite this partnership in rule, the peripatetic Cnut was often absent in the 1020s, as a king of England, Denmark and Norway by the 1030s. The expanse of Cnut’s dominion and the involvement of Ælfgifu of Northampton and her sons remained complicating factors for Emma. Cnut’s son by Emma, Harthacnut, was sent to Denmark in 1028. After acquiring Norway, Cnut sent his first wife Ælfgifu and Swein to rule over the kingdom in his absence in 1030. This left Harald, his eldest son by Ælfgifu, his likely successor in England. Such an arrangement would not guarantee Emma’s continued prominence or safety in England, nor would it bode well for her sons from her first marriage, who were both still in Normandy. Edward and Alfred were another complicating factor. In 1033, a charter was written by Emma’s brother Duke Richard proclaiming Edward as ‘king’. He gathered a navy with the apparent intention of attacking England on Edward’s behalf, and restoring him to the kingship, though the fleet never made it to England.

By the early 1030s we see Emma in a complicated position. Though now presented unambiguously as a sharer in Cnut’s rule, affording her more influence than in her marriage to Æthelred, she had remained once again unable to assert the claims of her own sons over those of her husband’s previous marriage. Though she has queenly legitimacy, her eldest son has been sent to Denmark. The complexity of this burgeoning situation is compounded by the continuing survival of Emma and Æthelred’s sons in Normandy. After the death of Cnut in 1035, covered in part 2 of this biography, we will see the fallout from this excess of possible heirs come to fruition.

Suggestions for further reading:

Pauline Stafford, Queen Emma and Queen Edith: Queenship and Women's Power in Eleventh-Century England (affiliate link)

Ed. Alistair Campbell, Encomium Emmae Reginae (affiliate link)

Lisa Hilton, Queens Consort: England’s Medieval Queens (affiliate link)

Share this post