Ælfgif-who? provides short biographies of early medieval English women. Click on the podcast player if you’d like to hear this newsletter read aloud in my appealing Yorkshire accent.

How 'English' is Saint George? The real history of England’s patron saint

Today is the feast of Saint George, England’s patron saint. The official flag of England represents his most recognised symbol, the Saint George’s Cross, a red cross on a white background. A martyr saint who is now best known for his dragon-slaying, George has also become symbolic of England, ‘Englishness’, and more malevolently, English nationalism. This is despite legends placing his birth in Asia Minor hundreds of years before the nation of England existed, and his cult’s original development around his tomb in Palestine. Instances of devotion to St George’s cult can be found in early medieval England, but his status as England’s patron saint did not begin to develop until the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. So how ‘English’ is Saint George really?

The legend of Saint George has been developing for well over a thousand years, which means that, as is often the case, mythology and history have become intertwined. In terms of objective historical evidence, nothing is known of the real life of Saint George. Everything that has been surmised about his life and deeds has developed from a long tradition of conflicting accounts and outlandish legends.

Origins in the Levant

Tradition holds that it was on this date, 23rd April, in 303 AD, that George was martyred during Roman emperor Diocletian's persecution of Christians. He was apparently an officer in the Roman army, originally from Cappadocia in modern Turkey. The earliest known cult of devotion to Saint George developed in the sixth century in Lydda, Palestine, around his alleged tomb. Other sixth-century cults of Saint George were recorded in Jerusalem and Jericho (Palestine), Edessa and Constantinople (Turkey), and Bizani (Armenia), and his name is recorded in multiple inscriptions in Arabia and Syria. By the seventh century his cult was flourishing in the eastern Mediterranean: a Coptic church in Cairo (Egypt) was dedicated to St George, and the Archbishop of Crete composed a literary work in praise of him.

Cults of Saint George also developed further afield in this period - the first references to him in Frankish sources begin in the sixth century, as well as multiple church dedications - according to one seventh-century source, Queen Clothild, wife of Clovis, had a church built and dedicated to St George a century earlier. His cult travelled to the British Isles in this period, and the seventh-century bishop Adomnan of Iona reports miracles he performed at the site of his tomb in Lydda.

Tracing an English Saint George

His earliest appearance in an English source is in a martyrology by the eighth-century monk Bede, and it’s not until the tenth century when we find him again mentioned at Durham in a short prayer. But it is in works by Ælfric in the eleventh century that we first see attempts to Anglicise George, calling him an ‘ealdorman’ (an Old English term for a noble), and placing his origin in the ‘Shire of Cappadocia’. However, George does not make it into either of Ælfric’s volumes of saint’s lives written for the ‘English people’ - only one specifically for educating monks.1 Ælfric’s write-up of George’s life pre-dates any association with dragons, concentrating instead on his martyrdom.

Indeed, in the pre-conquest period Saint George was a martyr-saint among many, enjoying no special status in England. It was local martyr-saints and their equally local cults that flourished the strongest - Saint Oswald, Saint Edmund, and Saint Edward the Martyr to name a few - all of whom happen to be royal saints. The first saint to come close to ‘patron’ status in England was Edward the Confessor, a king whose cult flourished in the centuries after his death in 1066, not least due to his promotion by subsequent kings. Edward the Confessor was not a martyr, but due to his building of Westminster Abbey, and his queen Edith having a saint’s life written about him soon after his death, he had acquired a reputation for piety and chastity.

It was during the Crusades, the series of religious conquests undertaken by Christians aiming to expel Muslims and establish Christian dominance in the Holy Land, that George’s status as an army officer, and therefore a military saint, became particularly important. Some tales have emerged that link Saint George’s growing popularity to Crusader King Richard the Lionheart, but these are myths that originated in the Tudor period.2 Nevertheless, a book containing a Life of Saint George written by the Archbishop of Genoa in the 1260s soon circulated widely in England, and this popularised the story of Saint George slaying the Dragon, which had originally circulated in Georgia. George was no longer simply another Christian martyr, but had now become a symbol of both crusading and chivalry.

Unlike many exalted English saints, George was not a king. Nevertheless, it is through the monarchy that Saint George became an important figure in England. King Edward I used Saint George’s cross as an emblem for his army when he invaded Wales in the thirteenth century and subjected the Welsh to English overlordship. His grandson, Edward III, wishing to replicate his grandfather’s victories, also employed the emblem in his military exploits and on his naval ships during the Hundred Years War. In the 1340s he established the Order of the Garter, the highest chivalric honour, and made George its patron saint, outranking all other saints. In 1415, Saint George became associated with Henry V’s victory at the Battle of Agincourt. It was in this way that Saint George became synonymous with the military might of the English crown.

In terms of the veneration of George by the people, which was widespread, his association in the later medieval period was still less about Englishness or monarchy and more about dragons. Churches, hospitals and trade guilds were dedicated to George, with local processions on Saint George’s Day acting out his slaying of the dragon and rescue of a princess. It was this popular imagination of George, as well as his associations with military victory and chivalry, that ensured the survival of his legend post-reformation. As the English monarchy rejected Catholicism, the veneration of saints declined, but George, as a symbol, lived on.

The post-medieval Saint George

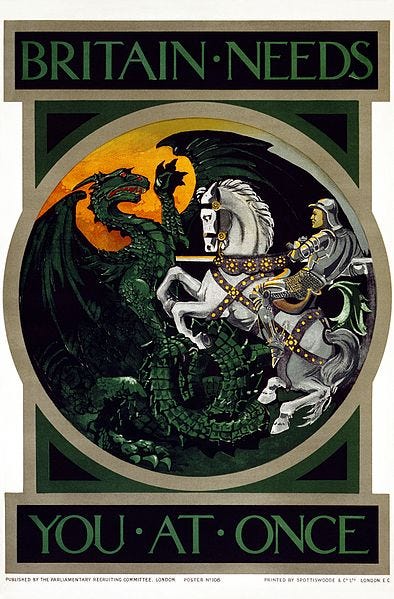

Since then, George has remained a symbol of England, though rising and falling in popularity as political circumstances changed. The revival of medievalist aesthetics mixed with the neo-chivalric Empire-building of the Victorian era resurrected George - so to speak - as a jingoistic nationalist figure. This continued into the First World War, when Saint George was used a symbol to recruit young men to the British Army. The prevailing relevance of George to propagandists was still the dragon - which could symbolise whichever ‘evil’ they wished to defeat. This is certainly far more persuasive an image than the reality of muddy trenches and death by machine gun.3

It is unsurprising that as a figure associated with crusading, empire, monarchy and British military victory, Saint George is the darling symbol of the far right in England. During the Second World War, British POWs who joined the SS named their unit The Legion of St George. The Neo-Nazi group League of St George, devoted to the racist ideals of Oswald Mosely, was founded in 1974. A poll conducted in 2012 revealed that a quarter of the English population see Saint George’s flag primarily as a symbol of racism. He is still a politically relevant figure, with the leader of the Labour Party Keir Starmer repeatedly asserting his enthusiasm for St George’s Day and the English flag, and still being doubted in his patriotism by the right wing press this week.

So how English is Saint George?

Really, all we can be certain of about the real George is that he wasn’t English, and that he never set foot on English soil. The early history of his mythology asserts that he is from Turkey - his cult developed in Palestine, was fostered in the Levant, and he is considered a prophet by Muslims. He is not only the patron saint of England, but is also venerated in Georgia, Portugal, Aragon, Catalonia, Brazil, Bulgaria, Russia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Montenegro, Lebanon, Palestine, Syria, Ethiopia, Egypt, Armenia, Greece, etc, etc, etc. But when it comes to this saint, the ‘facts’ are almost irrelevant - he is an entirely legendary figure, whose meaning and symbolism has been transformed by those who wished to use him. With no concrete historical reality to cling to, he can only be his associations. In that way, George is an English figure as much as he belongs to anyone. He’s a symbol of nationalism and racism as much as dragon-slaying and martyrdom.

That he can be claimed for anything and anyone is both the appeal and the danger with Saint George. And yet, it serves as a reminder that anyone trying to claim him for their own nefarious ends is only clinging to their own illusion.

Jonathan Good, The Cult of St George in Medieval England (Boydell, 2009), p. 31-32.

Ibid., p. 37-38.

Ibid., p. 146.

Recommended Reading:

If you’re interested in this topic, I heartily recommend Jonathan Good’s book The Cult of St George in Medieval England, a detailed but accessible exploration of this topic that can be picked up online for a very reasonable price.

Share this post