Ælfgif-who? provides short biographies of early medieval English women. Click on the podcast player if you’d like to hear this newsletter read aloud in my appealing Yorkshire accent.

Eostre: Pagan fertility goddess or complete fabrication?

It’s often said that the modern celebration of Easter is connected to an early medieval ritual about bunnies and eggs surrounding a pagan goddess called Eostre, which the English church stole and made Christian.

If you search the word Eostre on the internet out of curiosity, Google generates a ready explanation about who she is, right at the top of the search results:

‘Eostre is the pagan fertility goddess of humans and crops. The traditional colors of the festival are green, yellow and purple. The symbols used are hares and eggs, representing fertility (because we all know that bunnies breed like, well, rabbits) and new life.’

The explanation does not come from a particularly authoritative source, but from a staff writer at the St. Cloud Times, a small newspaper in Minnesota in the US. This article entitled ‘Traditions of Easter and cultural appropriation of Eostre’, that the Google algorithm has really decided to push for some unknown reason, makes a series of other claims about the ‘ancient’ mythology surrounding Eostre - that she mated with the solar God, that she is associated with dragons, and perhaps most controversially, that ‘Christianity should be embarrassed that it has needed to embellish its Easter tradition by appropriating pagan symbols and rituals for its own use.’1

The trouble with this article is that not a single one of these claims has any basis in historical evidence. Let’s explore what we can know about the mythology of Eostre, and her association with Easter.

To begin with, I’ll outline all the historical evidence about pre-Christian worship of the goddess Eostre: In his book The Reckoning of Time, the eighth-century historian Bede gives an explanation as to the names of each of the months. Bede tells us that Easter used to be called Paschal, after the Hebrew word for Passover, the Jewish feast that Easter was adapted from:

‘Eosturmonath has a name which is now translated ‘Paschal month’, and which was once called after a goddess of [the English people] named Eostre, in whose honour feasts were celebrated in that month. Now they designate that Paschal season by her name, calling the joys of the new rite by the time-honoured name of the old observance.’2

And well… that’s it! These two sentences by Bede are the sum of the historical evidence for the existence of the goddess Eostre. No mentions of eggs or bunnies, fertility or anything else. We need to take the Christian monk Bede’s word for it that he was au fait with pre-Christian practices to even believe that the month was named after the goddess Eostre and not something else entirely.

There are some reasons to trust Bede on this. Versions of the name Eostre were used among speakers of Germanic languages around this period and in the centuries after. Also, the Old English word ‘eastre’ shares features with words that refer to dawn goddesses in many other languages, such as the Hindu goddess Ushas, the Greek goddess Eos, and the Roman goddess Aurora.

However, there are other possible explanations. Ronald Hutton, expert in pre-Christian religion, argues that:

‘It is equally valid, however, to suggest that the Anglo-Saxon ‘Estor-monath’ simply meant ‘the month of opening’ or ‘the month of beginnings’, and that Bede mistakenly connected it with a goddess who either never existed at all, or was never associated with a particular season but merely, like Eos and Aurora, with the dawn itself.’3

Not only does being sceptical of Bede mean we can’t rely on the historicity of a goddess Eostre, but the idea that early medieval non-Christians even feasted during March and April is also uncertain. So much for Christianity appropriating a ‘Pagan’ festival then.

There is one further pressing question - where did all the ideas surrounding Eostre and her connection with eggs, bunnies, etc. come from, if not from the historical sources? This is more complicated.

In documents written between Bede and the nineteenth century there is no mention of Eostre. Then in 1835, Jacob Grimm (of fairytales fame) wrote about her in his book Deutsche Mythologie. Grimm connects Eostre with the Old High German word for the Easter festival, Ostara. He claims, with no evidential basis, that Ostara was a goddess, and that it is from her ancient feast that we get Easter eggs. Grimm was engaged in a nationalistic project to promote, and often manufacture, nationalistic German folk myths. Grimm’s goddess Ostara has since been treated as further evidence for Bede’s goddess Eostre, despite the fact that Ostara is made up based on the information provided by Bede!

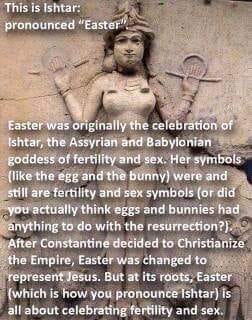

Then, in 1853, a further fabrication muddied the waters. Alexander Hislop, a Scottish protestant, published an anti-Catholic tract that claimed, again baselessly, that the word Easter came from the ancient Mesopotamian fertility goddess Ishtar! This factoid often circulates online as a meme and has entered the public consciousness, despite being completely made up.

These two falsehoods have provided a springboard for much more postulating and mythmaking about Eostre, often coming from neopagan and new age sources, and leading to misunderstandings of history such as the myriad of strange information thrust at us by Google, courtesy of the St Cloud Times. Eostre has even since become associated with the ‘pre-Christian’ Easter bunny (or Easter hare), despite no such tradition appearing in recorded history until 1678!

So was Eostre a pagan fertility goddess or a complete fabrication?

In terms of spiritual practice, there is no harm that I can see in creating a worship practice intuitively around different springtime traditions. There is no definitive reason to disbelieve Bede about the pre-Christian worship of a goddess Eostre, even if the evidence is tentative. If you feel like honouring Eostre at this time of year, that’s great!

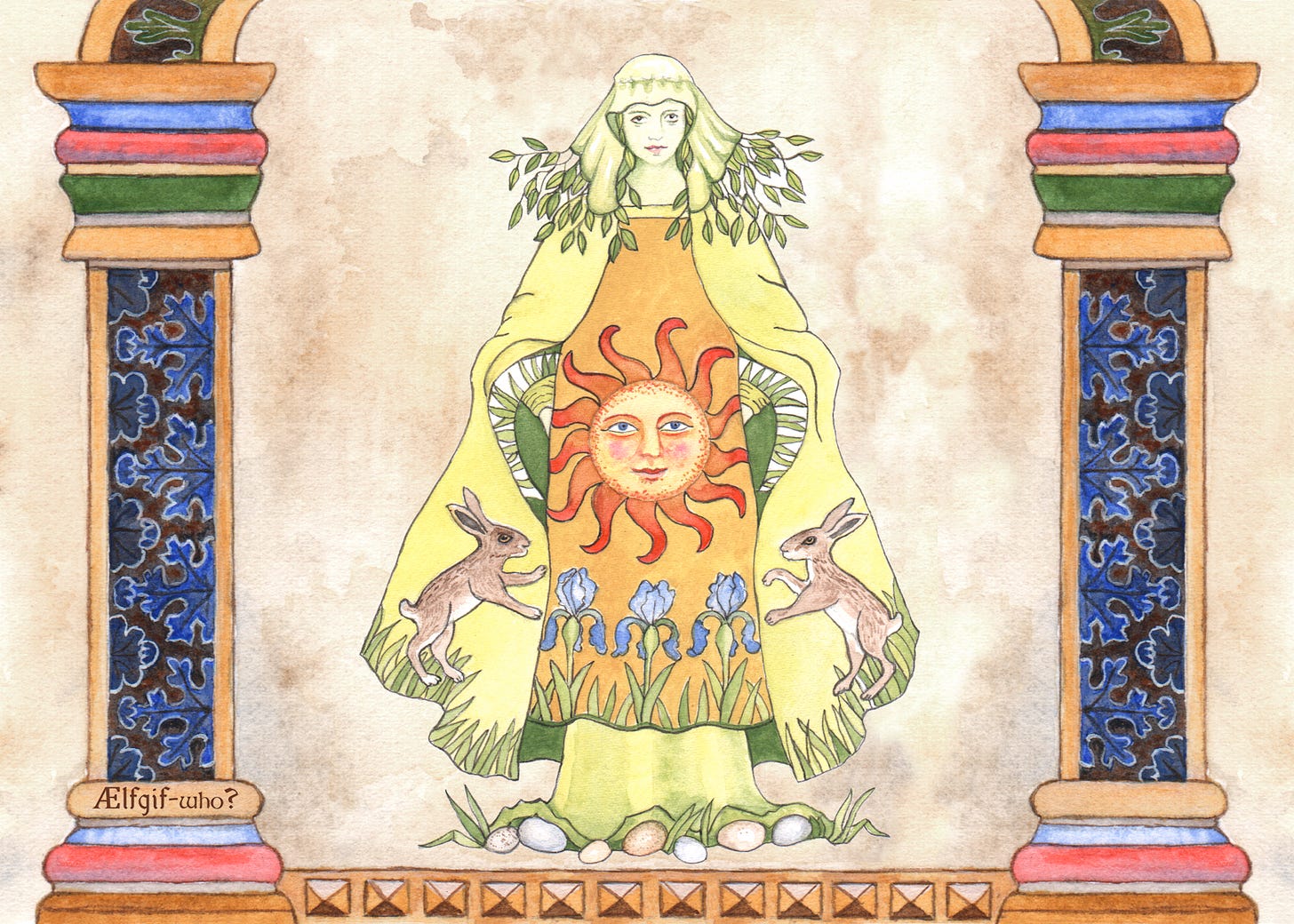

Problems arise when baseless suppositions and fabrications are mistaken for historical facts. This can get messy, especially when the initiators of such fabrications have overt ethno-nationalist agendas, or when the falsehoods are used to sow division. Online images of Eostre overwhelmingly depict her as a human woman with pale skin and fair hair, and when taken together they present a racialised, almost aryan fantasy of this “Germanic goddess”. This depiction has nothing to do with pre-Christian beliefs, and such false ideas, especially when presented as having a historical basis, have the capacity for real harm. The truth of the matter is, we have very little historical evidence for pre-Christian practices.

Accusations of ‘cultural appropriation’ in this context, such as from the author of the St Cloud Times article, would be problematic even if they weren’t based on fabrication. ‘Cultural appropriation’ is a useful concept for describing the unacknowledged adoption of elements of a minority culture by a dominant culture. Are we to suppose that the minority culture that has been wronged here is pre-Christian Britons who lived over a thousand years ago? Or is it actually ancient Mesopotamians? Neither group currently exists to be wronged in such a way. It is a misuse of the term.

Of course I am not claiming that pre-Christian practices were not suppressed by Christian converts. But surely, the fact that so little is known of early medieval pre-Christian beliefs in England, and the fact that we have to turn to brief and untrustworthy Christian sources to try and understand these practices, reveals much more about the suppression of these customs by the church than the claim that a fake spring festival was the basis of modern Easter. Only through carefully surveying the evidence can we do true justice to the lost cultural practices of the past.

Interested in more historical mythbusting? Read more:

Saint Bega: Begu, Heiu, Beyu or beag? A legendary Irish saint who may have been many women... or a bracelet

Ælfgif-who? provides short biographies of early medieval English women every two weeks. Click on the podcast player if you’d like to hear this newsletter read aloud in my appealing Yorkshire accent. Saint Bega: Begu, Heiu, Beyu or beag? A legendary Irish saint who may have been many women... or a br…

Trans. Faith Wallis (1999).

Ronald Hutton, The Stations of the Sun: A History of the Ritual Year in Britain (OUP, 1996), p. 180.

Share this post