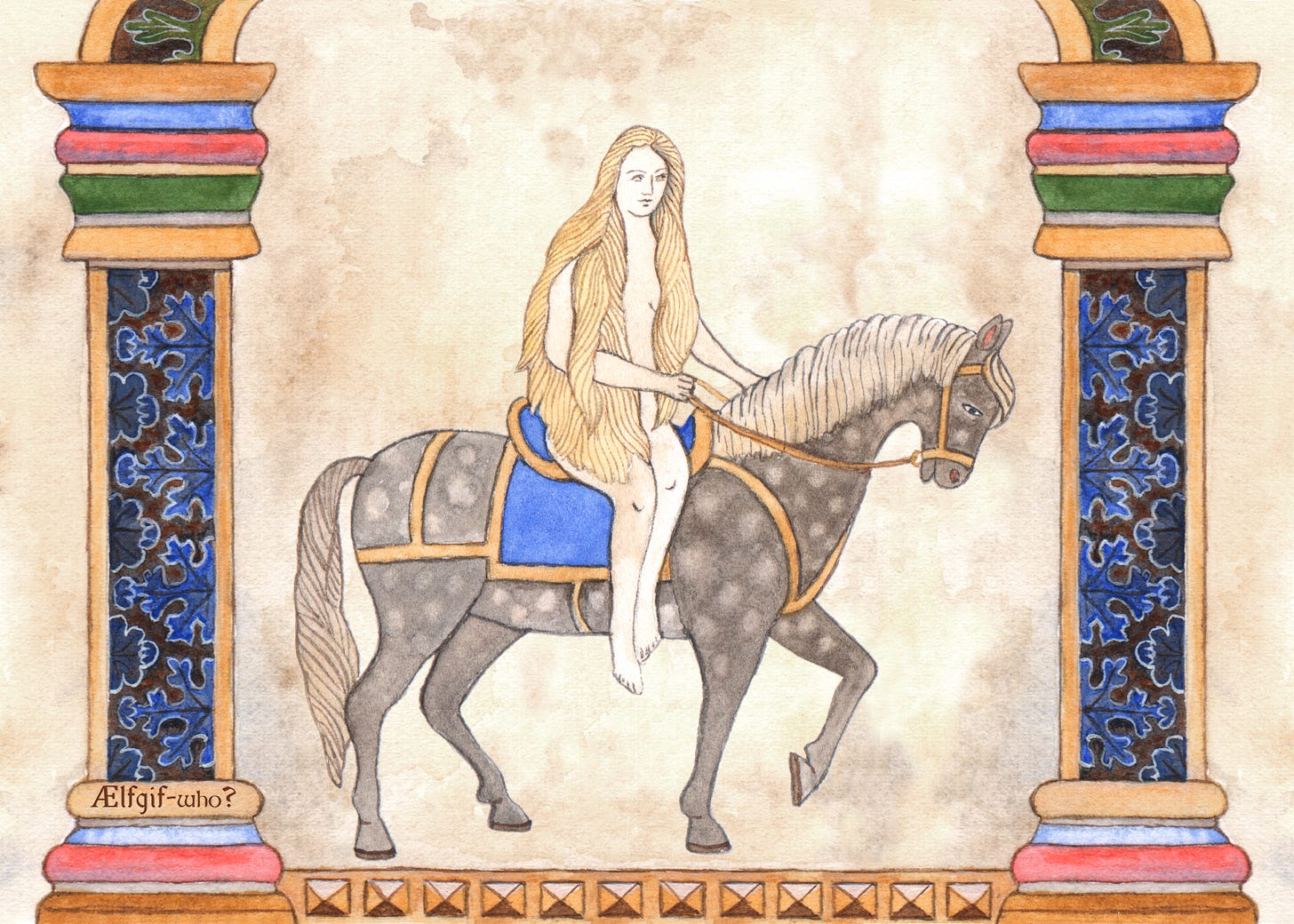

Ælfgif-who? provides short biographies of early medieval English women every two weeks. Click on the podcast player if you’d like to hear this newsletter read aloud in my appealing Yorkshire accent.

Godgifu: The Bare Truth Behind the Lady Godiva Legend

Many of you will be familiar with the legend of Lady Godiva, a medieval noblewoman who rode through the streets of Coventry naked, covered only by her long hair. The story goes that Godiva’s greedy husband was exacting punitive taxes on the townspeople, and she plead with him to lower them. He agreed, though on the absurd condition that she ride her horse naked through the town. Godiva defiantly called her husband’s bluff. To maintain her modesty, she issued a request that the residents of Coventry avert their eyes, though one man, a tailor named Tom, violated this request and was miraculously struck blind. So arose the phrase ‘peeping Tom’. The compassionate Godiva gained the triumph over her greedy husband and secured tax relief for the people of the town.

Less well known are the life and deeds of the real medieval woman on whom this story was based, who lived centuries before the fictitious legend of ‘Godiva’ was ever recorded. ‘Godiva’ is a Latinisation of the Old English name Godgifu. Godgifu, who lived from c.990-1067 was the wife of Earl Leofric of Mercia, and she was a major and influential female landholder in England before the Norman Conquest. Godgifu is perhaps less romantic, less miraculous, and less appealing to the male gaze than the iconic Lady Godiva - but she’s real. It’s time to revisit Godgifu’s life, her reputation, and her relationship to an eventual mythology that she never could have imagined.

Godgifu married Leofric in around 1010. At this time he was a younger son of Leofwine, an ealdorman (a high-ranking nobleman), who had been promoted into his role by the king. The Danish conquest of England by Cnut that occurred between 1013-16 would radically change the fortunes of Godgifu and Leofric in the first years of their marriage. Leofric’s elder brother, Northmann, was killed on Cnut’s orders. Leofric thus inherited his father’s title when he died in the mid-1020s, and by 1032 he had been promoted to Earl of Mercia – a huge earldom in what is now the midlands of England. He held this title through the reigns of four kings: Cnut, Harold, Harthacnut and Edward the Confessor. Godgifu’s social position thus rose both unexpectedly and meteorically from the wife of an ealdorman’s younger son to the wife of the Earl of Mercia.

As powerful members of the nobility, Leofric and Godgifu were extremely affluent. Land ownership meant access to the profits of natural resources, farmland, industry, and slave labour. The scale of their charitable donations to the church gives some impression of their considerable wealth. Recorded as 'the earl's wife', Godgifu is associated with her husband in the endowment and rebuilding of the church of Stow St Mary, Lincolnshire in the 1050s, which was said to have been in ruins since it was burned down by Vikings. The twelfth-century chronicler Orderic Vitalis says that Godgifu gave 'her whole store of gold and silver’, and this is said to include a necklace which was worth 100 silver marks. The Evesham Chronicle also names Leofric and Godgifu as founders both of Coventry, and also of the church of Holy Trinity, Evesham, to which they apparently gave a crucifix with figures of the Virgin Mary and St John the Evangelist.

Godgifu outlived her husband, who died in around 1057, and she is recorded as a major landholder in the Domesday Book, the land survey produced after the 1066 Norman Conquest of England. Noble wives often held some dower lands, allocated for the widow to inherit for her upkeep after her husband’s death, but there is evidence that Godgifu also held onto lands in Worcester that were seized from the church illegally by her father-in-law Leofwine, which her husband had promised would be returned on his death. Instead of giving up these lands, she endowed the church with expensive vestments and ornaments and promised to pay the annual dues from the estates and to return them on her own death. Once again, these promises amounted to nothing, as the lands were seized from Godgifu by her own grandsons, Earl Edwin of Mercia and Earl Morcar of Northumbria. She probably died after the Norman Conquest in around 1067, outliving both her husband and her son, Ælfgar. Godgifu’s status as an extensive landowner was not typical even for very elite women in pre-conquest England, and was a result of a combination of her family’s unexpected rise in status and her widowhood.

Godgifu went some way to try and ensure her lasting reputation for piety trough the endowment of churches, despite holding property that was illegally obtained from the church. In the centuries after her death tales of her beauty, virtue and devotion to the Virgin Mary developed, though it is not until the early thirteenth century that we see the story of Godgifu transformed into Godiva’s naked horse ride. Roger of Wendover in his Flores Historiarum writes that:

The countess Godiva, who was a great lover of God's mother, longing to free the town of Coventry from the oppression of a heavy toll, often with urgent prayers besought her husband, that from regard to Jesus Christ and his mother, he would free the town from that service, and from all other heavy burdens; when the earl sharply rebuked her for foolishly asking what was so much to his damage, and always forbade her ever more to speak to him on the subject.

And while she on the other hand, with a woman's pertinacity, never ceased to exasperate her husband on that matter, he at last made her this answer, 'Mount your horse, and ride naked, before all the people, through the market of the town, from one end to the other, and on your return you shall have your request.' On which Godiva replied, 'But will you give me permission, if I am willing to do it?' 'I will,' said he.

Whereupon the countess, beloved of God, loosed her hair and let down her tresses, which covered the whole of her body like a veil, and then mounting her horse and attended by two knights, she rode through the market-place, without being seen, except her fair legs; and having completed the journey, she returned with gladness to her astonished husband, and obtained of him what she had asked; for earl Leofric freed the town of Coventry and its inhabitants from the aforesaid service, and confirmed what he had done by a charter.

Roger of Wendover is well known for his exaggerations. This story is not corroborated by earlier sources and cannot be verified; thus historians must treat it simply as a colourful myth. Over the years, elements have been added to the legend, such as the fourteenth century miraculous version where Godiva is invisible, a sixteenth century modest version in ballad form, in which she requests that all the townsfolk stay indoors so as not to see her nakedness, or the late eighteenth century moralistic addition of Peeping Tom, who is struck blind, or sometimes dead, after trying to glimpse her naked body.

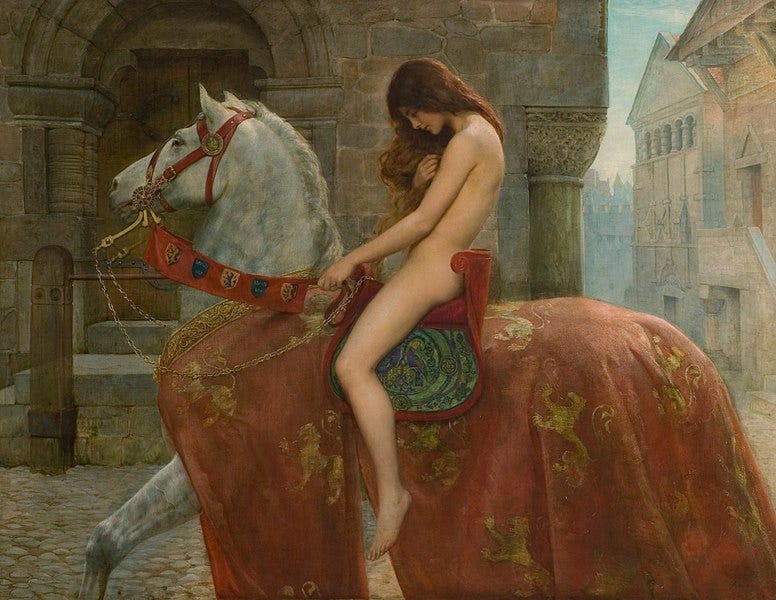

Despite the crux of this story being Godiva’s modesty and miraculous determination not to be seen, the image of her nakedness has become iconic. Her ride through the streets was performed as a procession in Coventry from the seventeenth century. Artists, sculptors, and composers have attempted to bring her to life through art, turning her into a sex symbol, and the rest of us into inadvertent peeping Toms. Godiva represents that perfect, paradoxical balance of chaste and erotic femininity that only a legendary woman might achieve.

It might seem as if the later legend of Godiva has very little to do with the real evidence we have about the eleventh-century noblewoman and landowner Godgifu. However, some links can be made between the two. Godiva’s lack of adornment in her nudity would have seemed shocking to a medieval audience, not necessarily because nudity was an indication of sexual promiscuity, but because nobility was indicated by outer wear, like clothing and jewellery. By removing these, Godiva was not only removing her clothes, but also her status. Her nudity in this story does not function as a moral failure, but the converse, as an act of piety, in which she lowers herself in order to help those less fortunate, and her hair covers her ‘like a veil’ to protect her modesty. This kind of medieval piety through renouncing earthly goods is also present in the act of the real Godgifu giving away her precious necklace, an important symbol of status for elite women, to Coventry Abbey, as well as great quantities of gold and silver. Within the legend of Godiva and the real life of Godgifu there is a common thread of unadornment as a way of elite and wealthy women expressing religious devotion. Renouncing a necklace is merely a symbolic gesture of deprivation from one of the wealthiest women in the country.

The real Godgifu was more complex, less virtuous, and probably less publicly naked than the Godiva of legend. She was a social climber, a member of the elite, and a woman highly concerned with her own reputation. Her eventual identification with the beautiful, naked Godiva comes by the way of a sense of her personal piety and social generosity that may be just as mythical. However, Godiva is not the first political woman to be remembered primarily within an erotic myth, nor will she be the last.

Suggestions for further reading:

A great place to start would be Daniel Donoghue’s Lady Godiva: A Literary History of the Legend. Donoghue is an expert in Old English and Middle English literature.

‘Roger of Wendover's Flowers of History: Comprising the History of England from the Descent of the Saxons to A.D. 1235; Formerly Ascribed to Matthew Paris’, Volume 1, translated by John Allen Giles

Share this post