Ælfgif-who? provides short biographies of early medieval English women every two weeks. Click on the podcast player if you’d like to hear this newsletter read aloud in my appealing Yorkshire accent.

Hugeburc: The Earliest English Woman Writer, Who Hid her Identity in a Secret Code

In 1931, a scholar named Bernhard Bischoff decoded a cypher placed between two saints’ lives in an early ninth-century manuscript from Eichstätt, Germany. The lives were written about Saints Willibald and Winnebald, two English brothers who in the eighth century became, respectively, the Bishop of Eichstätt and Abbott of Heidenheim, both in the modern day region of Bavaria.

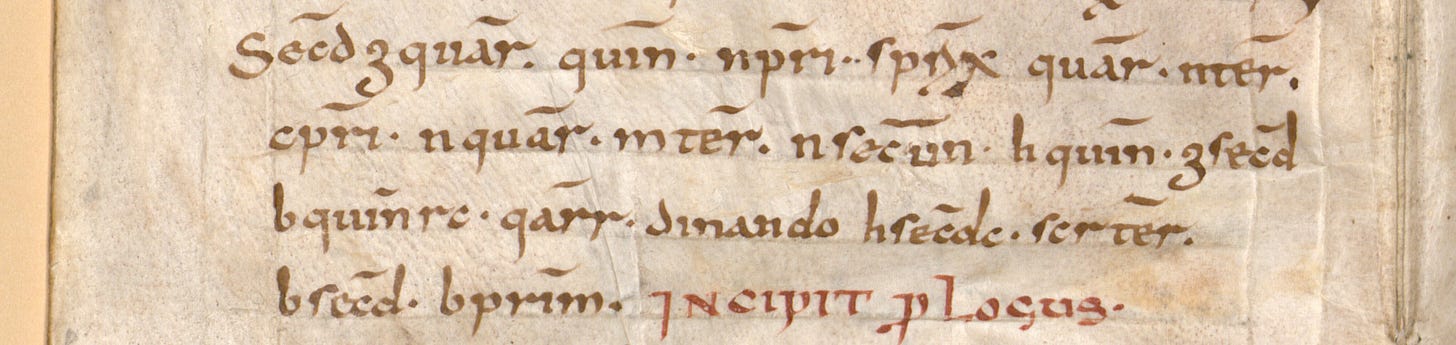

The cypher reads:

Secundumgquartum quintumnprimum sprimumxquartumntertium cprimum nquartummtertiumnsecundum hquintumgsecundum bquintumrc quartumrdinando hsecundumc scrtertium bsecundumbprimumm

Bischoff worked out that all vowels had been replaced by ordinal numbers - ‘second, g, fourth, fifth, n, first, s…’ and so on. Each of these numbers could be replaced with the corresponding vowel, to make the Latin sentence:

Ego una Saxonica nomine Hugeburc ordinando hec scribebam

I, a Saxon nun called Hugeburc, have written this

Thus, it was only in 1931 that Hugeburc’s name was revealed, and could finally be attributed by scholars to these important texts.

The two texts tell us more than just her name. Saints Winnebald and Willibald had a sister, Saint Walburga. When Winnebald, Abbot of Heidenheim died in 761, Walburga inherited the monastery, at which point it became a double monastery, admitting both men and women. Abbess Walburga brought a group of nuns with her from England: Hugeburc tells us that she was one of these nuns, and that she is a ‘humble’ kinswoman of these three English saintly siblings. She witnessed first-hand some of the posthumous miracles of Winnebald at Heidenheim, which she wrote about in her saints life.

In June 778, Willibald, now in his seventies, who was visiting his sister’s monastery, dictated his life experiences to Hugeburc, giving a particularly detailed account of his pilgrimage from Southampton to Jerusalem in the 730s. Hugeburc enthusiastically recorded the details of this journey, paying particular attention to his arrival in the Holy Land, and his visit to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. This text became her Life of Willibald.

Hugeburc is the earliest known English woman author of a full-text literary work. Unlike her name, her femaleness is not hidden in the text, but it is not celebrated either. Hugeburc writes:

And yet I especially, corruptible through the womanly frail foolishness of my sex, not supported by any prerogative of wisdom or exalted by the energy of great strength, but impelled spontaneously by the ardour of my will, as a little ignorant creature culling a few thoughts from the sagacity of the heart, from the many leafy, fruit-bearing trees laden with a variety of flowers, it pleases me to pluck, assemble and display some few, gathered – with whatever feeble art, at least from the lowest branches – for you to hold in memory.1

While this self-deprecating introduction is not the most feminist statement for the earliest known English woman writer to make, it must be put in context of a tradition in which hagiographic writers often stress their own unworthiness to write their saints lives, in order to emphasise the superior saintliness of their subjects. Hugeburc was likely using her sex as a convenient way to present herself with humility. Hugeburc has an unusual and overly complex writing style, which frequently employs rare words and phrases, alliteration and similes, and this has been interpreted by some scholars as flawed Latin or evidence of the ‘feeble art’ she claims. However, others have seen her style as ambitious and innovative. Indeed, it is often assumed that the unconventional writing styles of some early female authors reflect a poor knowledge of Latin, rather than merely demonstrating a different approach to Latin composition or a different skill set.

Hugeburc demonstrates her skill at cryptography by hiding her name in a secret code. This hidden authorial statement is also consistent with the humility she shows throughout her texts. For all her protestations about her own ability, in her own unconventional way Hugeburc laid claim to the texts she produced, ensuring that her name lives on over 1200 years later, and indicating at least a little pride in her accomplishments.

Suggestions for further reading:

I cannot recommend the following book enough for people who want to know more about early medieval women writers: Diane Watt, Women, Writing and Religion in England and Beyond, 650-1100, 2019

And I also really recommend: Peter Dronke, Women Writers of the Middle Ages (affiliate link), 1984

Translation by Peter Dronke, Women Writers of the Middle Ages (Cambridge, 1984)

Share this post