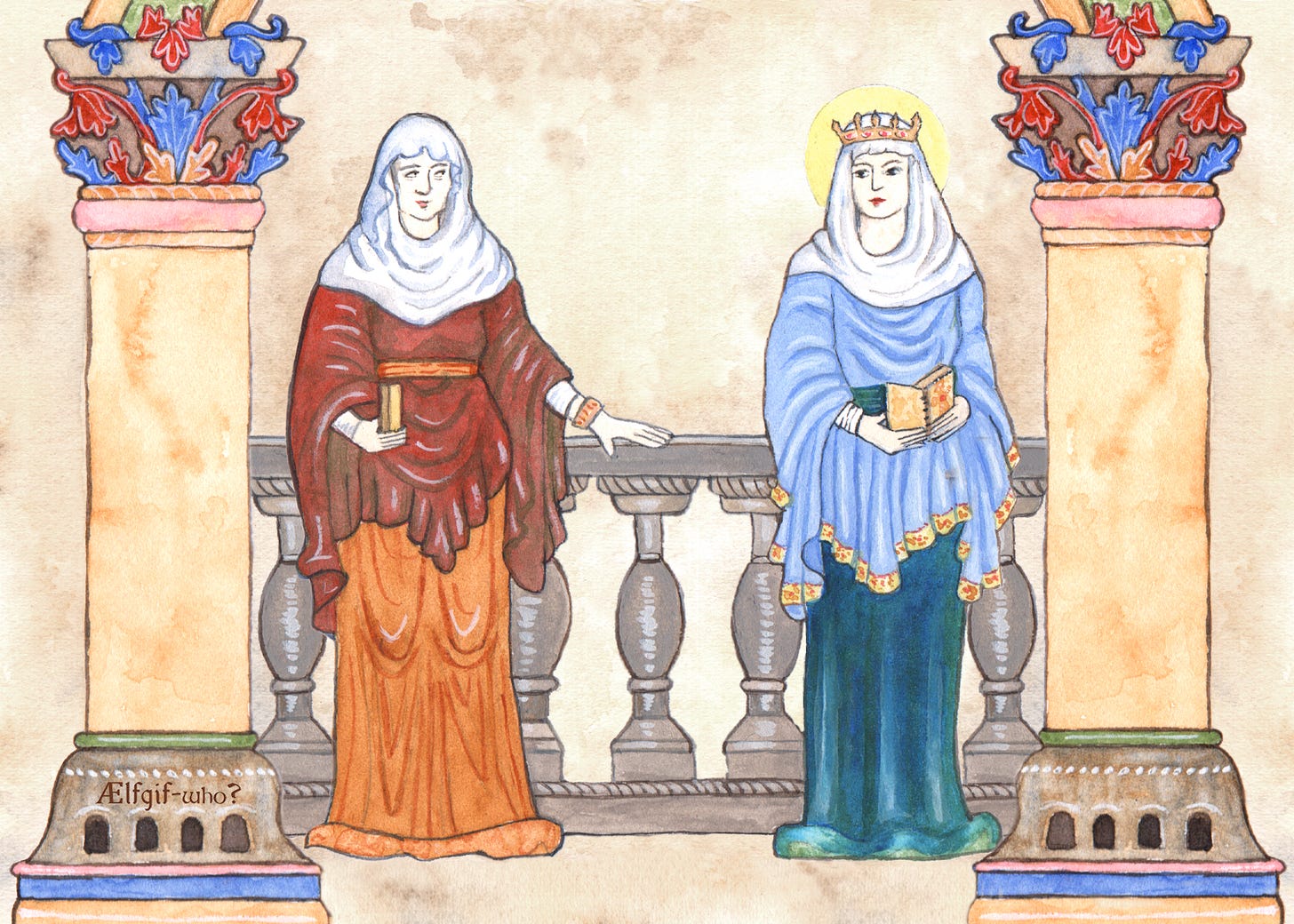

Ælfgif-who? provides short biographies of early medieval English women every two weeks. Click on the podcast player if you’d like to hear this newsletter read aloud in my appealing Yorkshire accent.

Wait, Saint Æthelgif-who? The real history of two medieval women revived in 21st century political discourse

On the 9th December, Conservative MP and Leader of the House of Commons Jacob Rees-Mogg referenced a medieval woman during Business Questions. After being faced with a question from Scottish National Party MP Anum Qaisar about the UN’s International Corruption Day and several of the British government’s recent corruption scandals, Rees-Mogg said:

Today is also the feast day of St Æthelgifu, who is the daughter of Alfred the Great and who became an abbess; I am more tempted to offer a debate to celebrate the virtues of one of England’s leading saints.1

Rees-Mogg then went on to praise Britain’s reputation on corruption and its corruption laws. While this probably isn’t the best place to delve into a lengthy discussion of corruption, it is the perfect place to discuss Æthelgifu: what Rees-Mogg got right about her, and (most importantly) what he got wrong.

There was a woman called Æthelgifu who was the daughter of King Alfred. We know about her from a mention in Alfred’s biography, written by a monk called Asser. Asser tells us that Alfred had five children who survived infancy: Æthelflæd, Edward, Æthelgifu, Ælfthryth, and Æthelweard. Asser then tells us that:

Æthelgifu, devoted to God through her holy virginity, subject and consecrated to the rules of monastic life, entered the service of God.2

Alfred’s will, which survives, leaves two estates to his ‘middle daughter’, who we can assume is Æthelgifu even though she is not named. There is also a charter that states Alfred gave Shaftesbury to his daughter because she was ill or infirm, but this has been found to be a later medieval forgery and its contents are therefore questionable.

Unfortunately, that is the extent of the contemporary historical information we have about Æthelgifu. While the main biographical details Rees-Mogg stated are corroborated by the historical sources, any claim of her sainthood is very questionable. In this period there was no formal canonisation process - saints were simply figures who came to have miracles associated with them after they died, and who were worshiped because of it. We have no Saints Life written about Æthelgifu, no documents that state she is a saint, no reports of miracles, and no evidence of a cult celebrating her.

This is not to say that she was not regarded as a saint in the decades after her death - it was common for abbesses, especially those who were the first abbesses of their institution, to go on to be celebrated as a patron saint. But with no information either way, to claim that she is a one of ‘England’s leading saints’, is misleading. To claim that somebody could lead a debate about her virtues, when all we know of her is a cursory mention in a single book, is plain wrong.

Despite Æthelgifu’s relative obscurity in the historical record, Queen Ælfgifu, who had been married to Æthelgifu’s nephew King Edmund, did become patron saint of Shaftesbury after her death in 944. Is it possible Rees-Mogg confused the two women? Is Ælfgifu the leading saint to whom he refers? Let’s explore what we know about Ælfgifu.

Little is known of Ælfgifu’s life or career as Queen of England. Charter evidence suggests her mother was a woman named Wynflaed, who seems to have been associated with Shaftesbury. The date of her marriage is not known, and she seems to have played a negligible role in her husband’s rule of the kingdom according to charter evidence. She died in around 944, possibly in childbirth. It is only after her death that she becomes notable in the source material. The late tenth-century chronicler Æthelweard reports that miracles had taken place at her tomb in Shaftesbury Abbey, hence her becoming its patron saint. Even after she was replaced as Shaftesbury’s patron saint by Edward the Martyr after his body was reburied there in 979, her cult continued to flourish. This is indicated by her inclusion in around a dozen pre-conquest liturgical calendars and saints litanies. Despite the details of Ælfgifu’s life not surviving in the extant source material, the number of sources from this period that do mention her illustrate just how much she eclipsed Shaftesbury’s founder, Æthelgifu.

It would be understandable if someone were to confuse these two women. Both royal, both connected to Shaftesbury, and with two similar names. “Ælfgif-who” itself is a joke about just how confusing and common pre-conquest English names can be. You may even remember that the last edition of this newsletter was also about a completely different pair of women called Æthelgifu and Ælfgifu, from the same period!

However, given the biographical details provided by Rees-Mogg and the fact that Ælfgifu was a queen and not an abbess, I don’t think a simple confusion of the two is possible. More likely is that Æthelgifu’s name made it into some modern compilation of saints somewhere along the line along with the date 9th December. She is not included in the major collections of saints, including the Roman Martyrology. Her name is included in the 1921 Ramsgate Book of Saints, and comes up along with the date 9th December on some Catholic websites, though none substantiate her inclusion or provide any sources about her life or deeds. The reason for her inclusion remains a mystery.

All this demonstrates that when evoking Æthelgifu during his parliamentary statement and espousing her importance as an English saint and her virtuous deeds, Rees-Mogg couldn’t have had knowledge of these things. I think it’s important to point this out. Not because people aren’t allowed to make mistakes about history, but because Rees-Mogg’s ultimately insubstantial evocation of Æthelgifu was political grandstanding. Æthelgifu’s supposed saints day, her virtue and crucially her ‘Englishness’ were contrasted with a negative criticism of the British government, and used to deflect it. This deflection was ultimately a misuse of a historical figure.

***Correction - a previous version of this post (and the podcast) says that the two women were sisters-in-law. This was a mistake caused by my brain falling out. Ælfgifu married Æthelgifu’s nephew. Glad I didn’t say that in parliament…

Not finished Christmas shopping yet? Don’t forget you can purchase a gift subscription of Ælfgifu-who for a friend or loved one! Paying for a subscription means you can support the newsletter and makes sure I can keep writing.

Have a lovely December and I can’t wait to see you all again in the New Year!

Asser’s Life of King Alfred, translated by Simon Keynes and Michael Lapidge.

Share this post