Ælfgif-who? provides short biographies of early medieval English women every two weeks. Click on the podcast player if you’d like to hear this newsletter read aloud in my appealing Yorkshire accent.

Æthelthryth, Part 2: A warrior saint who slaughtered Vikings and Normans with her sisters-in-arms

Part 1 looked at what we know about Æthelthryth’s life and what happened in the decades right after her death. Born a princess of East Anglia in the early seventh century she was married to a nobleman, widowed, and went on to become the Queen of Northumbria. She refused to consummate her two marriages and entered into the monastic life, becoming the Abbess of Ely in 670 and serving for seven years until her death from the plague. Sixteen years after she died her body had not decomposed. She was transferred into a new marble coffin which was miraculously the right size for her.

Usually a historical biography takes into account what happened during someone’s life, from their birth until their death. The word biography comes from the Ancient Greek βίος (bios), ‘life’, + γράφω (grapho), ‘to write’. It’s difficult to fit many early English saints into this genre, as sainthood by definition is something that happens after death, when miracles are reported and a cult is fostered by a church or a local community. The lives of many figures who feature in Ælfgif-who? are not well documented in sources from when they were alive, but new stories about them emerged in the sources many years after their deaths. This is not only the case with saints like Hild and Eanswith, but also women who became the subjects of retrospective scandals and controversies, like Queen Eadburh, and Queen Ælfgifu. When dealing with early medieval history, biography necessarily becomes not just about life, but legacy.

While Æthelthryth’s life is fairly well documented through Bede’s Ecclesiastical History, her posthumous legacy is so extensive that I’ve had to write a Part 2 to explore it. The Liber Eliensis, or ‘Book of Ely’, compiled by a monk in the twelfth century, elaborates on Æthelthryth’s life and her legacy in some detail using older source material. Looking at how Æthelthryth was regarded in the centuries after her death reveals a lot about those who wished to remember her and keep her legacy alive. Most importantly, it gives us an opportunity to think about the many female relatives of Æthelthryth - sisters, half-sisters, nieces and great-nieces - who became involved and implicated in her sainthood. In the century after her death she was remembered by Bede primarily for her virginity and incorruptible body, but by the twelfth century she had also become a warrior saint, a symbol of protection and resistance against Vikings and Norman invaders.

Fostering a Female Family Cult:

Part 1 touched upon the translation of Æthelthryth’s body from her wooden coffin to a marble one sixteen years after her death, how she was found to have not decomposed, and her doctor’s testimony that her wounds had healed. It is worth re-focusing this incident on the woman who decided to have Æthelthryth reburied - her sister Seaxburh. Seaxburh’s life shared some features of that of her sister: she was also a queen, having been married to King Eorcenberht of Kent, and she became abbess of Ely in widowhood after her sister died. Unlike Æthelthryth she was not a virgin - evidence suggests she had two sons who became kings of Kent, and two daughters who became saints, which is probably why she receives considerably less praise from Bede. She was also not a reluctant queen like Æthelthryth, and sources point to her acting as queen regent for her sons Ecgberht and Hlothere - though this political experience would have set her in good stead for managing the monastery at Ely.

Æthelthryth was not the first of her sisters to have her body translated to a new resting place and found to be in perfect condition. Æthelthryth and Seaxburh’s sister Æthelburh, and their half-sister Saethryth, had both become nuns and then abbesses at Faremoutiers-en-Brie. Bede tells us that seven years after Æthelburh’s death in 664, her body was moved and found to be incorrupt. Seaxburh’s daughter Eorcengota was also a nun at Faremoutiers, and may have written to her mother to tell her of this miracle. The incident likely provided the inspiration for Seaxburh’s translation of Æthelthryth and the reports of her miraculous incorruption. This action should not be underestimated as an astute political move by Seaxburh as abbess of Ely - this miracle cemented Æthelthryth’s saintly reputation and led to the development of her cult, which endured for centuries. Fostering saints’ cults could be a huge boon for monastic sites, earning them a prestigious reputation and establishing them as important pilgrimage sites.

Seaxburh may have also been considering her own posthumous reputation and that of her family. The move led to her becoming part of a group of saintly sisters, which eventually extended to saintly nieces and granddaughters. Saints’ cults must be fostered, and these female familial networks loom large in Æthelthryth’s legacy at Ely. There is evidence that Seaxburh’s other daughter Eormenhild succeeded Seaxburh as abbess at Ely in widowhood, after the death of her husband King Wulfhere of Mercia. It is likely that during this period the cult of Saint Æthelthryth of Ely began to expand within Mercia, with two new foundations set up dedicated Æthelthryth in Lindsey, in modern Lincolnshire. Bede tells us that days after her death, Eormenhild’s body did not putrefy, but gave off a sweet smell. Eormenhild’s daughter Werburh was also reputedly an important religious figure in Mercia, heavily involved in Ely, and she was apparently put in charge of Mercian religious houses by her uncle King Æthelred. This may have also encouraged the growth of her great aunt’s cult. Werburh became a saint herself, and she was the subject of yet another miracle story involving her body being found not to have decayed when being translated to a new resting place.

Æthelthryth as Ely Icon:

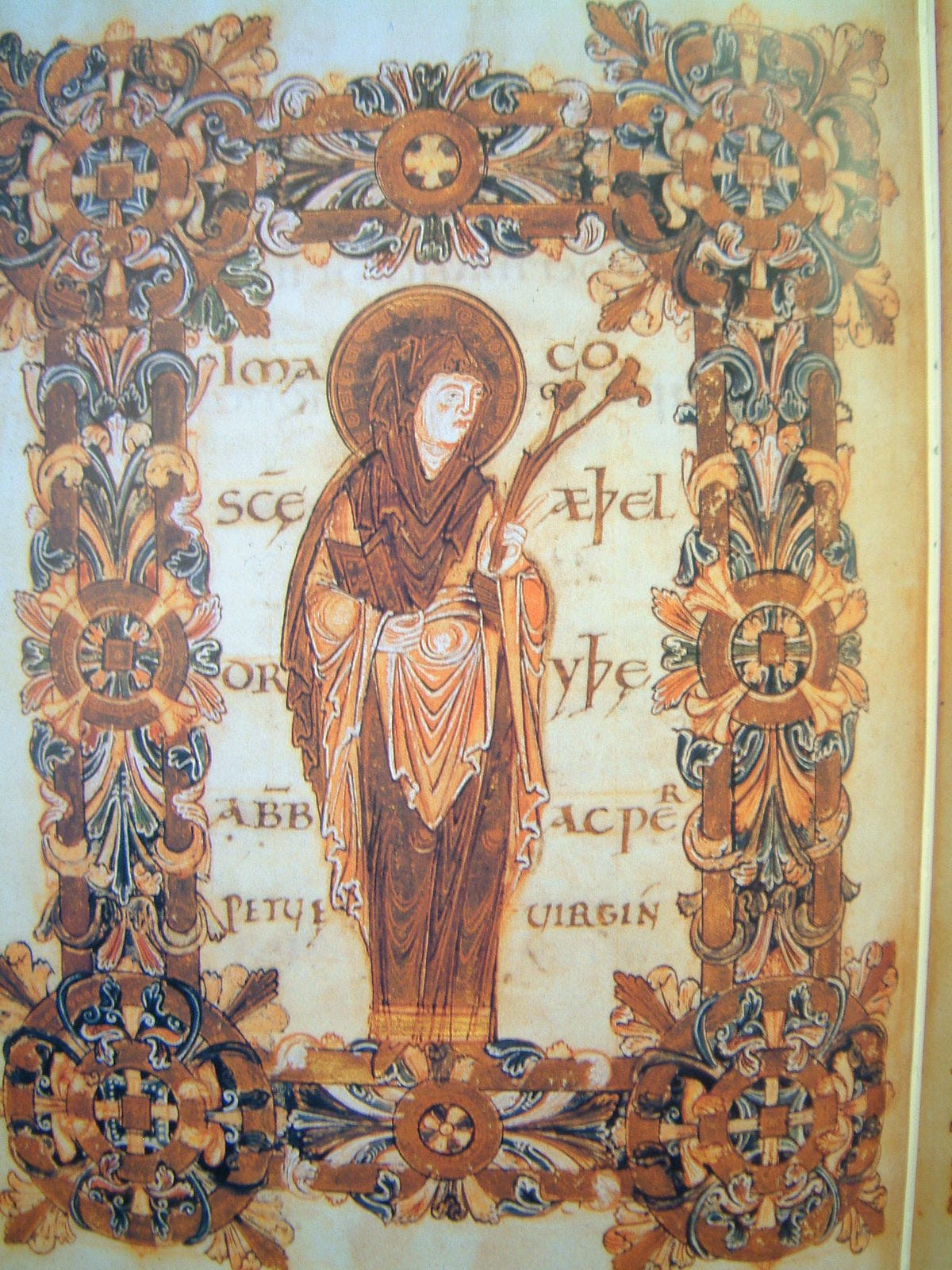

By the early tenth century, monasteries in general were in decline due to sustained Viking attacks. According to Ælfhelm, a priest at Ely writing in the tenth century, the Vikings attacked Ely and dispersed Æthelthryth’s cult in the late ninth century. This doesn’t seem to have had a long-lasting impact, and the shrine survived the Viking looting. By the mid tenth century a community of married priests was again active in promoting her cult. Bishop Æthelwold of Winchester was a leading figure in revitalising monasticism in the Benedictine tradition in the second half of the tenth century, and he took a particular interest in Æthelthryth’s cult. Æthelwold was interested in Bede’s view of the seventh century church, which could be seen as a kind of golden age of monasticism. He refounded Ely in c. 970, expelling the married priests who were maintaining Æthelthryth’s cult, and replacing them with Benedictine monks. Æthelthryth’s portrait and her saints day (on the 23 June) is included in a lavishly decorated Benedictional belonging to Æthelwold, with an inscription stressing her chastity and her ‘intact’ body in life and ‘incorruptible’ body in death.

The virginal and incorruptible Æthelthryth was the perfect figure to symbolise the displacement of the unchaste priests at Ely in favour of Benedictine monastic custodians, and Æthelthryth’s inviolate body was the perfect metaphor for the endurance of the monastery of Ely through Viking raids. But this posed a problem for Æthelwold and the new community. It was common to display saints relics in order for them to be seen and worshipped by pilgrims. However, removing Æthelthryth from her tomb hundreds of years after her burial and putting her remains on display could have risked shattering her reputation as incorrupt. To solve this problem, Æthelwold made the white marble sarcophagus itself the focal point of her shrine, holding a ceremony in which her coffin was brought into the church. This emphasis on her entombment created yet another layer of Æthelthryth’s impenetrability.

It was probably at this time that miracles were first recorded warning of the dire consequences of trying to open Æthelthryth’s tomb. The Liber Eliensis, using Ælfhelm’s earlier text, records that when the Vikings plundered Ely, one fierce raider attacked Æthelthryth’s tomb with an axe, hoping that there would be treasure inside. As soon as he had chipped off enough marble to create a small window into the tomb, he went blind and then he dropped dead. When the priests who had been dispersed by the Vikings returned eight years later, Ælfhelm witnessed one of them poke Æthelthryth’s body, through the hole made by the Viking, with a stalk of fennel, to try and see if she remained incorrupt. Finding that she was, he then attached a lit candle to a stick and poked this inside to see better, but as soon as he did this he went blind. The candle fell inside the tomb, and kept burning without setting her burial clothes alight. The blinded priest then pulled her undamaged clothes away from her body with a sharpened stick and cut at them with a knife, and his companions took hold of the cloth. A tug of war began between the men and the coffin, and Æthelthryth’s clothes were wrenched back into the coffin by a mysterious force back through the hole. In the following days, the text says, the priest’s entire family were killed by a plague, and his offending companions either died or went mad. Ælfhelm himself, a witness to these events, became paralysed and only regained his health when his parents took gifts to Æthelthryth’s tomb. The story of these men poking phallic objects through the hole in her coffin, removing and tearing at her clothes, is not a subtle metaphor for Æthelthryth’s preservation of her virginity. Nevertheless, these miracles justify the continued decision of the abbot of Ely not to allow anyone to open or look inside Æthelthryth’s tomb under any circumstances; a decision that enabled the monks of Ely to continue her reputation as incorrupt.

The relics of two other abbesses of Ely, Æthelthryth’s sister Seaxburh and her niece Eormenhild were put beside her, as well as another incorrupt virgin saint, Wihtburh, whose body was stolen from another monastery, and the claim was made that she was Æthelthryth’s other sister. This created a shrine not just to Æthelthryth but to a family of royal women associated with saintliness and incorruption. The new abbot of Ely had gold and silver jewel-encrusted statues of these four women made to display at the shrine.

Post Conquest Æthelthryth: Warrior Saint

In the years after the Norman Conquest of 1066, the leader of an anti-Norman rebellion called Hereward the Wake made Ely his base, which led to it being besieged. During this time, Saint Æthelthryth was transformed again into a symbol of resistance and protection. Rebels who joined Hereward would have to swear an oath to the cause on her tomb. The Liber Eliensis records miracles that demonstrate her continuing in this role in the decades after the Norman Conquest. One particular incident shows Æthelthryth not only to be a protector of Ely, but as an avenging assassin accompanied by her sisters. When a Norman noble called Gervase was particularly harsh in his treatment of Ely, condemning or imprisoning anyone who spoke against him:1

…St Æthelthryth appeared in the form of an abbess with a pastoral staff, along with her two sisters, and stood before him, just like an angry woman, and reviled him in a terrifying manner as follows: 'Are you the man who has been so often harassing my people - the people whose patroness I am - holding me in contempt? And have you not yet desisted from disturbing the peace of my church? What you shall have, then, as your reward is this: that others shall learn through you not to harass the household of Christ.' And she lifted the staff which she was carrying and implanted its point heavily in the region of his heart, as if to pierce him through. Then her sisters, St Wihtburh and St Seaxburh wounded him with the hard points of their staves. Gervase, to be sure, with his terrible groaning and horrible screaming, disturbed the whole of his household as they lay round about him: in the hearing of them all he said, "Lady, have mercy! Lady, have mercy!" On hearing this, the servants came running and enquired the reason for his distress. There was a noise round about Gervase as he lay there and he said to them, "Do you not see St Æthelthryth going away? How she pierced my chest with the sharp end of her staff, while her saintly sisters did likewise? And look, a second time she is returning to impale me, and now I shall die, since finally she has impaled me." And with these words he breathed his last.

Despite Æthelthryth and her sisters becoming symbols for resistance against Norman oppression, the Normans themselves were keen to keep her cult alive at Ely. Norman abbots took over the monastery, and in 1106 the relics of the four women were moved to new shrines in the rebuilt choir, with Æthelthryth placed in the position of honour. In the late eleventh and early twelfth centuries many more texts about her and her miracles were produced, especially in the time of the first bishop of Ely, Hervey (1109–31), who is believed to have commissioned the Liber Eliensis.

St Æthelthryth's cult continued to be promoted at Ely throughout the medieval period. About a dozen churches other than Ely were dedicated to her. A fair was held there in June to celebrate Æthelthryth’s feast day, where ribbons and lace necklaces that had touched the shrine were popular mementos. It is thought that the items sold at Saint Æthelthryth’s fair, who is known as Saint Audrey, gave rise to the term ‘tawdry’, a contraction of Saint and Audrey, which describes something that is showy but cheap. That she would become best known for cheap necklaces is ironic given that, as explored in Part 1, wearing expensive necklaces weighed heavily on her conscience, and she believed this caused the bubonic tumour that was to kill her.

Saint Æthelthryth’s shrine at Ely was finally destroyed during the dissolution of the monasteries. It is not known what state her body was in when it was finally removed from its coffin, but I’m sure that her and her sisters ensured those responsible met grisly ends.

Ælfgif-who? has a new facebook page where you will see posts about women in the early middle ages! Please give it a like!

Liber Eliensis: A History of the Isle of Ely from the Seventh Century to the Twelfth (2005). Translation by Janet Fairweather.

Share this post