Ælfgif-who? is a newsletter and podcast about the lives of early medieval English women. Click on the podcast player if you’d like to hear this newsletter read aloud in my appealing Yorkshire accent.

Breguswith: Portents and Pendants

Breguswith, who lived in the seventh century, was the mother of two powerful and saintly Northumbrian women: Hild, the Abbess of Whitby and Hereswith, Queen of East Anglia. Though she had illustrious daughters, Breguswith herself has survived history only in one short anecdote. From the few sentences recorded by a monk a century after her death, a surprising amount can be gleaned about the circumstances of her life.

We know of Breguswith through one historical source alone: The Northumbrian monk and historian Bede, writing his magnum opus, the Ecclesiastical History, in the eighth century. Bede was very interested in Hild’s religious significance, and included many pages about her career as abbess of Whitby, though her mother Breguswith only gets a cursory mention. Bede records the story of a dream that Breguswith had when her daughter Hild was an infant, and her husband Hereric was murdered in exile.

The anecdote begins:

While her husband Hereric was in exile under the British king Cerdic, where he was poisoned, [Breguswith] had a dream that he was suddenly taken away, and though she searched most earnestly for him, no trace of him could be found anywhere.1

This first sentence alone prompts a number of important questions. Firstly, when exactly did Breguswith have her dream? That Hild was in her infancy (infantia) suggests that this occurred when she was under the age of seven, according to the stages of life laid out in Isidore of Seville’s Etymologies, a text with which Bede would have been very familiar. Bede tells us that Hild died in 680 at the age of 66. That would put Hild’s birth date in 614 and this incident, assuming Bede has a relatively accurate knowledge of events, between around 614 and 621. However, Bede’s assertion that Hild became a nun at age 33 and died at 66 has almost too perfect a symmetry and is likely an allusion to the convention that Christ died at age 33. This is probably meant to emphasise Hild’s Christian virtue and likeness to Christ, rather than biographical fact. On this basis we can’t be certain exactly when Bede places Breguswith’s dream, but we can place it somewhere in the early seventh century.

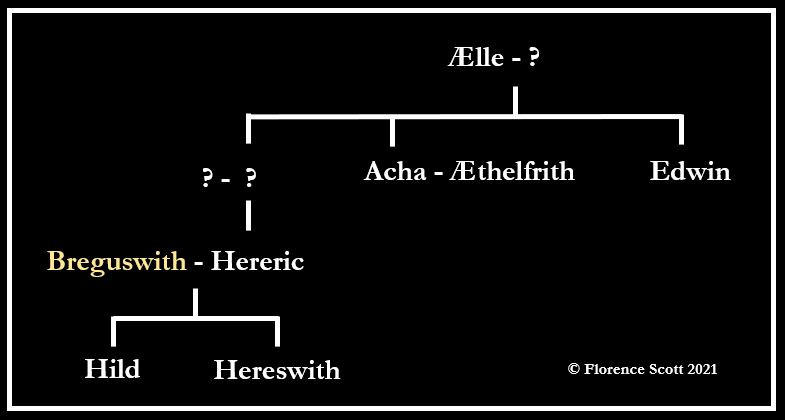

And what of Hild’s father, Hereric? Who was he, why was he in exile, and why was he poisoned? Bede informs us elsewhere that Hereric was the nephew of King Edwin of Northumbria (reigned c.616-32), making him the grandson of the late King Ælle of Deira (reigned c.560-88). This means that Hereric would have been a contender for the Deiran throne, and this may give us insight into firstly, why he was in exile, and secondly, why he was poisoned. In 604 the Bernician king Æthelfrith annexed Deira, uniting the two kingdoms into what became Northumbria, having married Edwin’s sister Acha, a Deiran princess. In 616 King Æthelfrith was killed in battle and King Edwin, Hereric’s uncle, took the throne. Hereric’s mere existence would have been a threat to either of these men, placing a large target on his head, and it is no wonder he was forced out of his own kingdom to seek safety with Cerdic, likely King Ceredic of Elmet. It seems he was not safe here after all, and he was disposed of as a possible rival to the throne.

That Bede has Breguswith lose Hereric in her dream indicates that he was killed during Hild’s infancy, and that she found out through this vision. It is clear that at this point Breguswith and her young daughter Hild, as well as her other daughter Hereswith, were not with Hereric in exile. Where were they? Did Breguswith stay in Deira with her two young girls, on the understanding they would be safe as they were girls, and thus not competitors for the throne? Did Breguswith flee to safety with her own family? Was she elsewhere in exile? Bede does not tell us explicitly of the personal trials that Breguswith faced during this period, how she felt or how she responded, but we can assume from these few sentences that her separation from her husband, first by exile and then by death, and the matter of her and her children’s safety, were her primary concerns.

Bede continues and completes the story of Breguswith’s dream, which prefigures the future success and saintliness of her daughter Hild:

But suddenly, in the midst of her search, she found a most precious necklace under her garment and, as she gazed closely at it, it seemed to spread such a blaze of light that it filled all Britain with its gracious splendour. This dream was truly fulfilled in her daughter Hild; for her life was an example of the works of light, blessed not only to herself but to many others who desired to live uprightly.

Though elsewhere in Bede’s Ecclesiastical History necklaces are used as symbols of worldliness (for example, Æthelthryth Abbess of Ely has a red sore tumour where she used to wear necklaces in her previous life as a queen), Breguswith’s necklace here is a portent of Hild’s future virtue and influence. In his commentary on the Song of Songs, Bede states that the neck is a fitting symbol for the teachings of the church and says that jewels worn around the neck can signify the divine scriptures and holy virtue. Some have speculated that although Bede tells us this dream took place when Hild was an infant, it is drawing from saintly narratives where the coming of a saint is predicted before their birth.

Although this dream narrative is almost certainly a conventional story used by Bede to praise the saintly Hild, archaeological surveys have found that jewellery could be an important signifier of a woman’s status and identity, and that different types of jewellery were bestowed at significant stages in life such as puberty or marriage – perhaps even the birth of a child. Necklaces would certainly have been important social signifiers to an elite woman like Breguswith.

Even with only one anecdote of a couple of sentences, we can glean that Breguswith was a young woman, with a young family, who was likely in a very precarious situation, separated from her exiled husband who had now been murdered. From very little evidence we know her name, her status, that she was widowed, and that she raised at least two daughters who grew up to be politically active and religiously devoted. Much of the historical discussion surrounding this short anecdote about Breguswith has focused on what it says about how Bede wanted to present Hild, who rightly cuts an important figure in the Ecclesiastical History and in modern histories of early medieval England. Less attention has been paid to Breguswith. Historians are often at the mercy of Bede’s whims, and he rarely tells us everything we’d want to know about the early medieval English women who appear in his narratives. However, I think it’s worth trying to paint a picture of those women for whom we have little evidence – and in Breguswith’s case a cursory mention with a bit of added context can be expanded into a portrait.

All quotes in this article are from the translation by Colgrave, from Bede, The Ecclesiastical History of the English People: The Greater Chronicle ; Bede’s Letter to Egbert, ed. by Judith McClure and Roger Collins (Oxford University Press, 1999). The anecdote under discussion in this newsletter concerning Breguswith is in Book IV. Chapter 23 (p. 212).