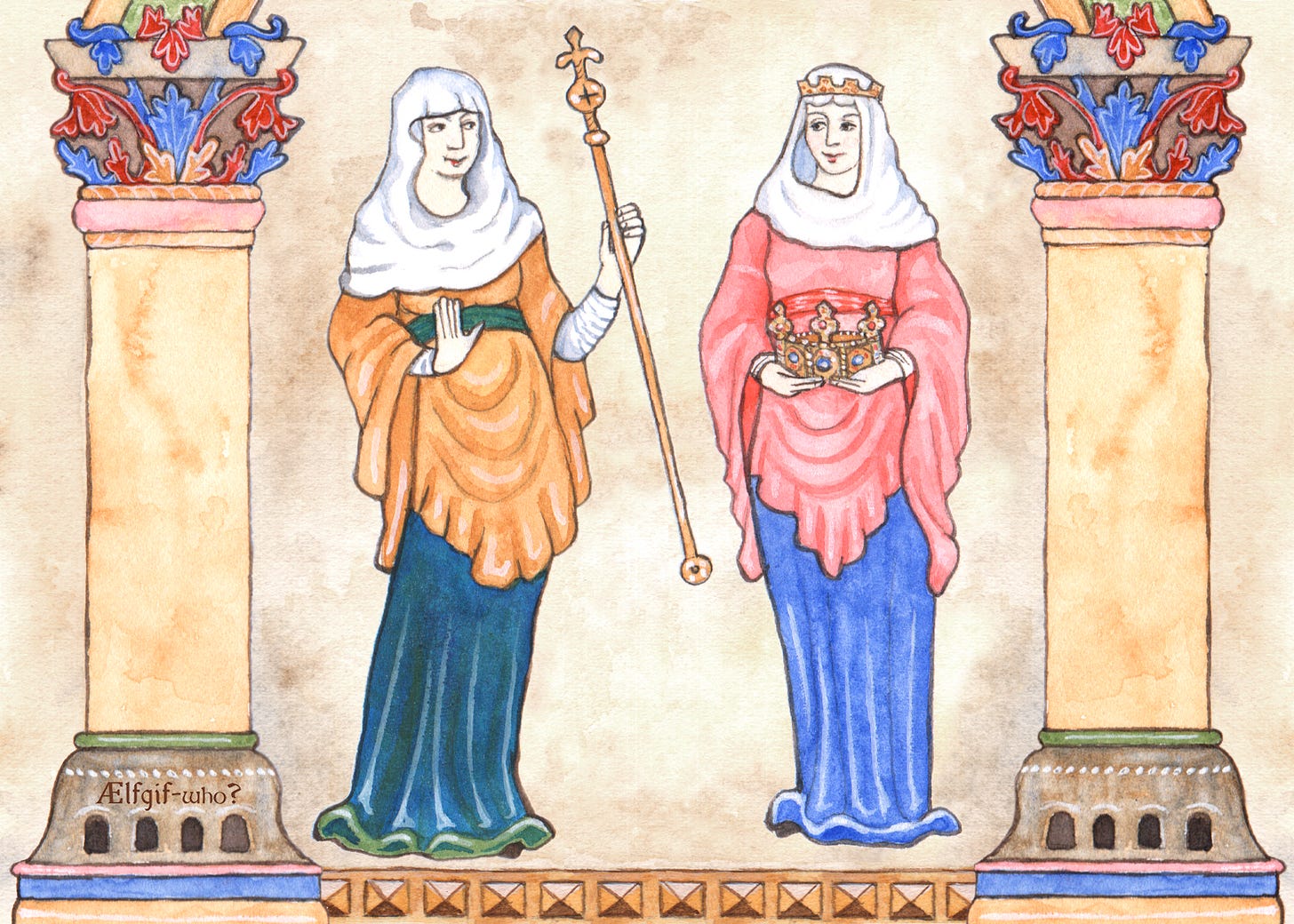

Ælfgif-who? provides short biographies of early medieval English women. Click on the podcast player if you’d like to hear this newsletter read aloud in my appealing Yorkshire accent.

Coronations and Queen Consorts: An Early Medieval Invention

You might have heard that there will be a ceremony happening tomorrow at Westminster Abbey, officially titled ‘The Coronation of His Majesty the King & Her Majesty the Queen Consort’. During this ceremony both Charles and his wife Camilla will be anointed on the head with holy oil, solidifying their existing roles as King and Queen of the United Kingdom. As I am a historian of queens and early medieval inauguration ceremonies, it would be remiss not to provide you with a brief history of the coronation and the queen consort’s role within it.

Queen consorts - queens who are married to kings - have been an important and constituent part of coronation ceremonies since their very beginning in the early middle ages. The purpose of anointing and crowning the king and queen is not really to officially designate them within their political roles - that happens upon the death of a previous monarch - but to add a religious and ceremonial significance to their hereditary rulership. This element of magic and ritual is what underlies royal power - otherwise, it would be very difficult to justify a political system that puts one family above all others.

Both the king and queen, for obvious reasons, are equally important in establishing and furthering dynasties. While Camilla is not related to the current dynastic heirs by blood, the practice of anointing her emerges from a tradition in which the queen had an equal role in creating and perpetuating a royal line. It is for this reason that queens were central to the original meaning and purpose of coronation ceremonies.

The modern coronation ceremony can trace its origins back to 751, when Pippin and Betrada were anointed King and Queen of the Franks. In 753 the royal couple were anointed again by the Pope, along with their two sons, Carloman and (the later emperor) Charlemagne. There are one or two anomalous examples of kings being anointed earlier than this date, but this was the ceremony that catalysed the existing 1300 year tradition. This ceremony emerged out of a need to establish legitimacy on shaky foundations - Pippin’s father Charles Martel had effectively usurped the previous dynasty, and though he was a powerful magnate, Pippin had no royal power until he created it. The ceremony was thus part innovation and part inspiration - kings such as Solomon had been anointed in the Bible, but not with the clear dynastic meaning of the 751 and 753 ceremonies.

In the earliest royal inauguration ceremonies, the most important part was the anointing with holy oil. These ceremonies only started to become known as ‘coronations’ from the eleventh century onwards. The practice of anointing kings and heirs was adopted fairly soon across the channel in England after it was established in Francia, though there is little evidence that this involved queens. The earliest surviving inauguration liturgies from England, known as the First English Ordo, only contains a king’s ceremony, which can be partly explained by their West-Saxon origin and the fact that the West Saxons afforded the wives of kings a conspicuously low status. These early English ceremonies also use a helmet, not a crown.

The earliest evident anointing and crowning of a queen of an English kingdom is that of Judith, the Frankish princess, Pippin’s great great granddaughter, who married two successive kings of Wessex. Her 856 ceremony upon her marriage to King Æthelwulf was significant, with the liturgy drawing heavily on themes of the royal couple’s joint fertility and Judith’s dynastic prowess as a Carolingian, despite the fact that Judith was only around 12 at the time of her marriage (her husband was around 50). This ceremony was heavily invested in the status that Judith had to bring to the West-Saxon royal line. It was this status that led her stepson to marry her after his father’s death - a scandalous move, but one which, if it had paid off, might have secured her dynastic prowess for his line.

Around the turn of the tenth century we have our earliest evidence for an English liturgy, again likely West-Saxon in origin, which includes both a king and a queen. It is at this point that we can view the anointing and crowning of queen consorts in England as somewhat standard - though by no means was a queen included at every inauguration. In this ceremony, used until after the Norman Conquest, the queen’s rite is a shorter and less substantial than Judith’s. This version of the liturgy, known as the Second English Ordo, can be viewed as the basis for tomorrow’s ceremony.

The idea of an anointed queen became a potent political tool in the years after this practice was established. There are examples of the children of anointed queens being afforded more legitimacy as heirs to the throne in succession disputes than the children of wives who had not been anointed. There are also examples of anointed queens, like Judith, marrying their husband’s successors - Queen Emma of Normandy married the conquering king Cnut after the death of her husband Æthelred II. Queens who had been anointed and crowned carried a magical sense of legitimacy and status that was appealing to kings looking to cement dynasties. While this was not a permanent sacred status - individual anointed queens could and did become irrelevant with changes in politics - having an anointed mother could be useful for an heir.

Figures looking to malign certain kings and factions could even use the idea of a king’s wife interfering with the sanctity of the anointing ceremony as a political tool. Those who opposed King Eadwig accused him of having an incestuous ménage à trois with his wife Ælfgifu and her mother at his coronation, throwing his crown on the ground in the process. From this anecdote we might view the coronation as an arena in which the king’s wife can either be seen as an asset, lending her sacred status to the legitimacy of the dynasty, or a liability, reflecting a king’s unsuitability to rule.

A lot of discussion around tomorrow’s coronation has focused on the legitimacy of Camilla’s queenship, which to some seems an even more pertinent question than Charles’ right to rule as king. Charles’ tumultuous time as heir to the throne was dominated in the British media by controversial stories of his infidelity, divorce, the untimely death of his first wife Diana, who was beloved by much of the British public, and his marriage to his former mistress, Camilla, a divorcee. The never-ending royal gossip mill, fuelled by recent fictional portrayals of these events in the TV series The Crown and the 2021 film Spencer, has revived these conversations.

Within the project of perpetuating a magic, ritual, inequitable, hereditary, dynastic monarchy, the queen consort inevitably acts as a foundational and inextricable facet of how royal power is justified - but also how it is criticised.

Share this post