Ælfgif-who? provides short biographies of early medieval English women every two weeks. Click on the podcast player if you’d like to hear this newsletter read aloud in my appealing Yorkshire accent.

Emma, Part 2: A Queen Mother of England Twice Over (1035-52)

Queen Emma cuts such an important figure in eleventh-century politics that I took the decision to publish her biography in two parts. The first part looked at Emma’s early life and her two marriages: to King Æthelred II and King Cnut. This second part covers her widowhood in 1035 until her death in 1052, including her involvement in the succession crisis following Cnut’s death, her role as the mother of two kings of England, and her commissioning of a literary work written in her political defence.

The Succession Crisis of 1035-37

Emma’s second husband King Cnut died in November 1035, sparking a succession crisis for the English throne. While the famous succession crisis following Edward the Confessor’s death in 1066 was caused by a lack of suitable heirs, this earlier crisis in 1035 was caused by a surplus. Cnut had two sons by Ælfgifu (Harold and Swein), and one by Emma (Harthacnut), and Emma’s sons by her first husband Æthelred (Edward and Alfred) were still living in Normandy. It is not known what arrangements, if any, Cnut made for the succession: if he designated a single successor this was certainly not reflected in the complex dispute that followed. This succession dispute placed Emma at the very centre of eleventh-century politics, as she worked to retain her position as queen. In 1041/2, she would later commission a political work known as the Encomium Emmae Reginae (In Praise of Queen Emma) that is an important source for this period, along with the C, D, and E manuscripts of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.

Harthacnut was away ruling Denmark on his father’s behalf when Cnut died in 1035. Harold, Cnut’s eldest son, took the throne just two weeks after his father’s death. One of his first acts as king was to go to Winchester, where Emma resided, and deprive her of the treasures she held. Despite this, a meeting of all the powerful men of the realm was held in Oxford to decide who should be king. The outcome of this meeting was that Harold should rule Mercia and Northumbria while Harthacnut should rule Wessex. But by 1036, Harthacnut had still not returned, and Emma likely held his part of the kingdom from her base at Winchester on his behalf. In this period of absence, Harthacnut’s position was reliant on supporters in England, not only his mother but also the powerful Earl Godwine, and Archbishop Æthelnoth of Canterbury, who the Encomium tells us refused to consecrate Harold as King of England. However, a letter, sender unknown, sent to Emma’s daughter Gunnhild at the German court where she was the queen of Henry III, informed her that Ælfgifu, Harold’s mother, was working on her son’s behalf to undermine Harthacnut’s rule, by holding feasts, sending gifts, and flattering nobles. Harthacnut was losing his grip on Wessex as opinion swung towards Harold, which meant that Emma was also losing her grip on queenship.

It was at this point in 1036 that Edward and Alfred travelled to England to their mother. They embarked separately, and while Edward made it to his mother at Winchester safely, Alfred was intercepted by Earl Godwine. Many of his retinue were violently murdered, and Alfred was taken to East Anglia where he was blinded, and then died. It may be that Godwine felt he was acting in the interest of Harthacnut, or that he had by then swapped his allegiance in response to the rising tide of opinion towards Harold. Emma would later claim in her Encomium that Edward and Alfred were lured to England by correspondence that falsely claimed to be from her. It is likely that Emma did make the miscalculation of inviting them to England to claim the throne, and wanted later to be dissociated from the responsibility of her son’s murder by pretending her letter was forged. By 1037, Edward had safely returned to Normandy, and Harthacnut was still in Denmark, waylaid by the political crisis ensuing after his half-brother Swein was expelled from his rulership of Norway. Emma had inadvertently caused the death of one son, alienated another, and her other son was nowhere to be seen. Harold now took the English throne with little obstacle, and Emma ‘was driven out without any mercy to face the raging winter’, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. She found refuge in Flanders, crucially not Normandy, perhaps revealing how her Norman relatives felt about her after Alfred’s murder.

A Return to Prominence? 1039-42

In 1039 Harthacnut sailed a fleet of ships to meet his mother in Bruges, indicating both that he was planning an invasion, and that Emma was involved in the plans. It was ultimately Harold’s premature death in 1040 that allowed Emma to return to prominence as queen of England, as Harthacnut now took the throne. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle tells us that Harthacnut had his brother’s body dug from its grave and threw it into a marsh. His rule was seemingly unpopular, with high taxation needed to maintain his large fleet of ships. It is perhaps for this reason that he invited his half-brother Edward to return from Normandy to rule alongside him in 1041.

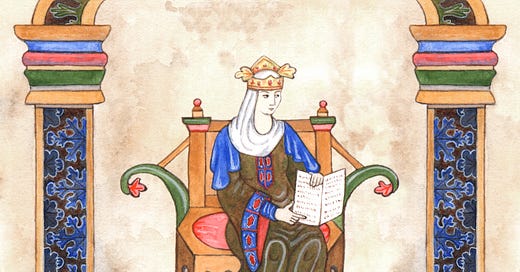

Having been Queen Consort twice over, Emma was now Queen Mother twice over, to two unmarried sons. After living through a tumultuous period in which one of her sons was murdered, her future was consistently uncertain, and she was deprived of her land and wealth twice and sent into exile, Emma must have felt in 1041 that she had finally found some stability. It is in this year that she commissioned the writing of her Encomium from a monk at St Bertin in Flanders, in order to tell the story of these events from her perspective. The frontispiece of Emma’s own manuscript of this work (see below) is an unambiguous show of power. While Emma is depicted centrally, enthroned, crowned, and being gifted the book by its author, her two sons, both kings of England, peer in from the periphery, looking almost like afterthoughts. She is the focus of this scene, in a way that contrasts with the depiction of her and Cnut as joint rulers on the Winchester Liber Vitae (see Part 1).

The Encomium does not overtly centralise Emma in the same way, beginning its narrative with Swein’s conquest of England in 1013. But a justification of Emma’s actions lies behind every passage. As well as putting her in the driving seat of her marriage to Cnut and exonerating her from blame for the murder of Alfred, its narrative casts aspersions on the parentage of the late King Harold, stating that Cnut’s first wife Ælfgifu was a mere concubine, and that Harold was secretly the child of a servant anyway. The text ends by describing the rule over England as a trinity – Emma and her sons. She places herself as the third part of their joint rulership.

Fall from Power? 1043-52

Until relatively recently, it was thought that Emma’s version of the Encomium was the only one to survive. However, in 2008, a second version was discovered. This appears to have been updated in 1043, adapting to a new political context. Harthacnut, like Harold, died relatively quickly after his reign began, after having a seizure at a wedding feat in June 1042. Edward was consecrated full king of England at Winchester in April 1043. The second version of the Encomium places Edward in a much more central position, likely reflecting Emma’s reliance on him for her political position. This rewriting to flatter Edward was apparently not enough. In November 1043, Edward had Emma once again deprived of all her wealth and land. She was attacked, without warning, by not one but three of Edward’s most powerful Earls – Godwine, Leofric, and Siward. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, this is because Emma had kept her wealth from him, and was ‘very hard to her son, in that she did less for him than he wished, both before he became king and after’. Later sources would explain these events by constructing a story in which she was accused of having an affair with a bishop, and was forced to undergo a trial over hot ploughshares to prove her innocence. Her fall from grace was short-lived and she was able to return to court in 1044, but her return to court was not a return to power. She made her last known public appearance in 1045 – the year Edward married Edith, the daughter of Earl Godwine, his brother’s murderer, with whom he would never have children. Edith took up the vacant role as queen. With most of her children dead, and with no grandchildren in England, Emma most likely retired to Winchester as a solitary widow. This is where she died in 1052, aged in her 60s or 70s. She was buried there with Cnut and Harthacnut.

In the 16th century, during the English Civil War, Roundhead soldiers scattered the bones held at Winchester. They were collected up and put into mortuary chests, though the skeletons were no longer identifiable. In 2012 a project began in which the bones were analysed, carbon-dated and reassembled. Though the remains of 23 individuals were discovered, only one skeleton, distributed among several chests, belongs to a woman. As she was mature when she died, and of the right period, this skeleton is believed to be that of Emma.

Emma’s actions appear quite ruthless – in 1017 she married her late husband’s conqueror, and in her widowhood she probably put her sons lives at risk in order to ensure one of them succeeded to the English throne. Rather than being motivated by motherly love, she arguably had a pragmatic approach to pressing her various sons’ claims to the throne, and yet seemed to favour Harthacnut over Edward. But her actions as wife and mother must be viewed in context. She probably had little to no say in either of her marriages. She also likely never had very close personal relationships with her children, who were all, for various reasons, sent away from her in childhood. Her safety, her wealth, her land, and her position, all depended on her continued career as queen. Of course, it is expected that a powerful man like Godwine would murder a rival to his favoured candidate for the succession, that Harold would take the throne and send Emma into exile, that Harthacnut would have his rival’s body dug up, and that Edward would deprive his own mother of her position. Ruthless actions are expected of powerful men who want to hold onto power. Emma, in fighting for her own political ends, was not as ruthless as many of the men around her. Our instinct might be to judge Emma primarily as a wife and mother rather than as a politician, while it might not even occur to us to judge Edward primarily as a son, or Harthacnut as a brother.

It was undeniably her family relationships that placed Emma in the position to become the individual around whom most of the events of the first half of the eleventh century transpired. But it was her actions as a politician, her reluctance to let go of power, and her will to influence events, that ensured that she became this individual. Despite her eventual fade into a quiet widowhood, her actions ensured that she has not faded in the historical record. To quote Professor Pauline Stafford: ‘Not all widows required three earls and a king to make them go gracefully. Nothing measures Emma’s power like her leaving of it’.1

Suggestions for further reading:

Pauline Stafford, Queen Emma and Queen Edith: Queenship and Women's Power in Eleventh-Century England (affiliate link)

Ed. Alistair Campbell, Encomium Emmae Reginae (affiliate link)

Lisa Hilton, Queens Consort: England’s Medieval Queens (affiliate link)

Pauline Stafford, Queen Emma and Queen Edith: Queenship and Women's Power in Eleventh-Century England, page 250. (affiliate link)

Share this post